I spent last weekend down in Fredericksburg, Virginia, taking part in the Center for Civil War Photography’s annual 3-day (and 3-D) Image of War Seminar.

People gather from all over America to see photographs, some in 3-D, of the Civil War–at the places where they were taken 150 years ago.

Friday was a particularly interesting day. National Parks Service Ranger John Hennessy led a wonderful tour of Fredericksburg: “City of Hospitals.” In 1862, 1863, and 1864, the small town of Fredericksburg and its buildings were transformed into hospitals–churches, public buildings, and private houses were filled with the wounded and dying. In 1864 alone, 26,000 men were treated in Fredericksburg for disease and wounds suffered in nearby battles. Many died.

I was interested in this tour because of my long-held fascination with the Civil War–perhaps the most important event in shaping America. However, I became even more interested as Green-Wood connections (inevitably) emerged. Where there is American history, there are ties to Green-Wood!

So, as we walked, John pointed out the Fredericksburg Courthouse. He mentioned that its architect was James Renwick.

I knew that name; Renwick was a very important 19th century architect who designed St. Patrick’s Cathedral and Grace Church, both of which still stand in Manhattan. He was also the architect of the Smithsonian Castle and the Renwick Gallery in Washington, D.C.

Then we turned up a side street, then another, and John, pointing out a brick building in the distance, noted that Civil War nurse Abigail Hopper Gibbons had ministered to the wounded there. Her name certainly rang a bell! I knew her story and exactly where she is interred at Green-Wood. A Quaker, she was raised in a home where good works were integral to life. She and her husband, abolitionists, were conductors of the Manhattan station (their home) on the Underground Railroad. I blogged about that two years ago. I know Abby’s story very well–I have featured her on several Green-Wood tours. She devoted herself to other causes, including temperance, aid to the poor, opposition to capital punishment, and the rehabilitation of prisoners. Elizabeth Cady Stanton said of her, “Though early married, and the mother of several children, her life has been one of constant activity and self-denial for the public good.” After a life of good works, Abby died in 1893.

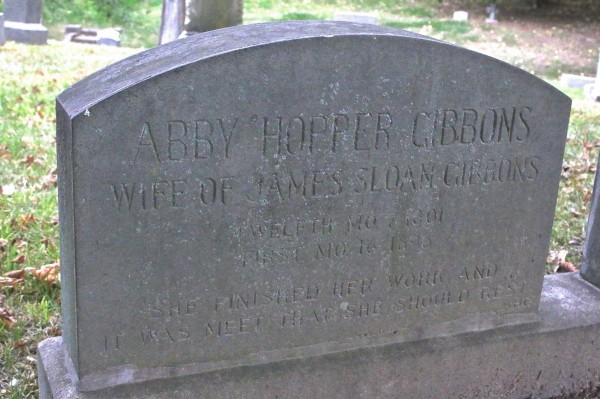

Here is her Green-Wood gravestone:

I also discovered five years ago that two ex-slaves are interred in the Hopper family lot–here’s that blog post.

In Green-Wood’s library, we have a two volume set of Abby’s letters: “Life of Abby Hopper Gibbons, Told Chiefly Through Her Correspondence,” edited by Sarah Hopper Emerson, her daughter. The book, published in 1896, contains two portraits of Abby. Here’s one showing her when she was 50 years old:

And this one, of her later in life:

Born in 1801, Abby Hopper Gibbons was 60 years old by the time the Civil War began. She and her daughter, Sarah Hopper Emerson, aware of the carnage, volunteered as nurses for the three and a half years during that war. With thousands and thousands of wounded soldiers, Union and Confederate, coming through Fredericksburg’s hospitals in the wake of the battlefield carnage of the spring of 1864, that little town was where these volunteer nurses had to be.

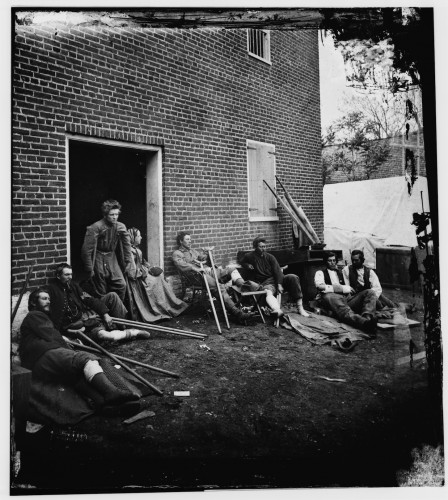

This is one of the iconic photographs of the Civil War:

Here’s a detail of this image–and that’s Abby Hopper Gibbons seated at center:

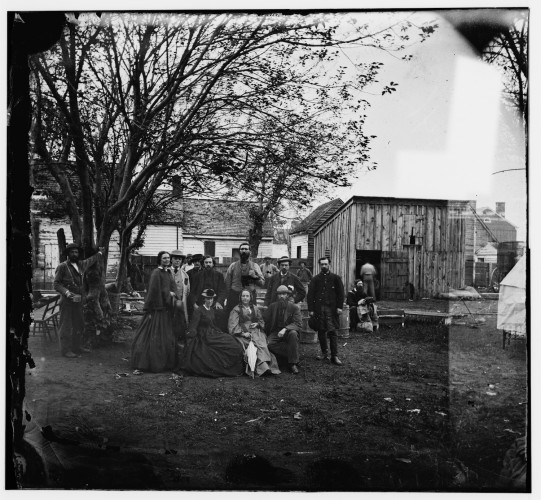

And this is a related photograph, likely taken the same day by the same photographer:

The U.S. Sanitary Commission was a private organization that, in the absence of any governmental organization up to the tasks of controlling sanitation in Union camps and treating the Union wounded and those felled by disease, stepped into the breach to do that work.

Here’s the Library of Congress’s catalogue entry for this image:

Glass, stereograph, wet collodion. Woman seated in center with umbrella identified as volunteer nurse Abby Gibbons of New York City with her daughter Sarah Hopper Gibbons seated at left (Source: descendant Andrea Schear, Oct. 2013) Photograph from the main eastern theater of war, Grant’s Wilderness Campaign, May-June 1864.

And here’s a closer look at the group:

The day after these two photographs were taken by James Gardner in Fredericksburg, Abby wrote from there:

. . . Started for this place 7:30 a.m., wading through mud to get to the ambulances. Such a road! and how wounded men ever bear the transportation is a mystery. Twelve miles of jolting which took seven hours and tired us nearly out! . . .

Reached Fredericksburg at 2 P.M. Had dinner and I was put into a Hospital at once. The whole town is filled with wounded. House after house, store after store, filled with men lying on the floor. I have about 160. We see nothing but frightfully wounded men.

And her daughter Sarah wrote a few days later:

You can form no idea of the work we had to do in Fredericksburg. I had a hundred and sixty men, all on the floor and not a bed to be seen; . . . packed so close that the men nearly touched each other; in one room with twenty-three men, fourteen amputations; not a breath of air until Mr. Thaxter knocked out the windowpanes and afterwards the sashes. We stole straw to fill ticks, stole boards to make bunks, stole bedsteads, took nails from packing boxes, and yesterday every man was comparatively comfortable. The filth exceeded anything you ever dreamed of–stench terrific. The Sanitary Commission has been the only decent feature of the place. Some of the Christian Commission have worked splendidly too. The Sanitary agents washed men, dressed wounds, and did everything. They have saved hundreds of lives . . . .”

Abby Hopper Gibbons led a remarkable life. It is very special to see her in these two unusual Gardner photographs, working as a Civil War nurse, doing the good works that characterized her life, and to read the words that she and her daughter wrote to describe their experiences.

Very nice. Love reading about Abby

Thanks. She was a fascinating person. Are you a descendant?