I recently came across a listing for an online auction for a half-plate daguerreotype photograph of Samuel E. Darling and his wife, Margaret Broadbent Darling. As per the listing, the seller had determined that they were married on August 4, 1851, and lived in New York City. Their identification was based on their names that were written on the mat surrounding the photograph and behind the photograph.

Here’s the seller’s description of this item:

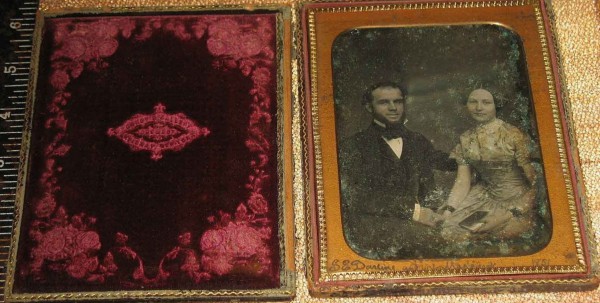

Mathew Brady 1/2 Plate Daguerreotype of newlywed couple Samuel E. Darling and his wife Margaret Broadbent. Ancestry indicates the couple were married on August 4, 1851 and lived in New York City. The case is an unpublished leatherette case depicting Wolfert’s Roost, home of author Washington Irving. . . . Image is heavily tarnished with possibly some emulsion loss (see photos). . . . Case has a repaired spine and is in overall good condition. Mat is engraved “S.E. Darling with wife Margaret 1851”. Behind photo also written similar identification. This is a rare and historic image, so this is an example of content over condition.

Learning from the description that we were dealing with a married couple who had lived in New York City in the mid-19th century, the possibility immediately occurred to me that they might be interred at Green-Wood. So I checked Green-Wood’s online database of burials and found these entries:

DARLING, SAMUEL, interment 1858-12-21, section 8, lot 4976.

DARLING, SAMUEL, interment 1874-01-16, section 8, lot 4976.

DARLING, MARGARET, interment 1881-08-05, section 8, lot 4976.

Notably, the Green-Wood database was also telling me that these were unusual 19th-century-New York names; of the 570,000 people interred at Green-Wood, most of whom were interred in the 19th century, no one, other than these three, was named Samuel or Margaret Darling.

Because both Samuel and Margaret are interred in the same lot, an indication that these might very well be our married couple, I concluded that the individuals who had been photographed were interred at Green-Wood. Having reached that conclusion, I then considered whether to bid on the daguerreotype. It had much going for it: first of all, though we do have quite a few photographs in our Green-Wood Historic Fund Collections of people who are interred at Green-Wood, primarily images on paper (mostly cartes de visite, cabinet cards, and stereoviews) of the famous, whether politicians, military men, etc., we have only a very few daguerreotypes of Green-Wood’s permanent residents, and none of what appeared to be a married couple. Further, the view was a half-plate, a rare large image, and was by the most famous of 19th century American photographers, Mathew Brady. Also, the case, with its image of Wolfert’s Roost, was a plus.

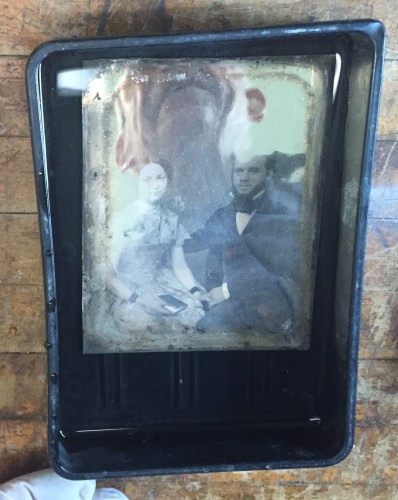

Against these pluses weighed the issue of the poor condition. The daguerreotype was invented by Louis Daguerre; its invention was announced in 1839. It was the first process that allowed for the permanent creation of photographic images. These images were preserved on a copper plate coated with silver; each image has remarkable detail and is one-of-a-kind. When it was time to take a photograph, chemicals were poured onto the polished plate, creating a surface sensitive to light. But images preserved on a metal plate are fragile–that’s why they are mounted in cases, behind glass–and this image clearly had condition issues. Here is another image of what the daguerreotype that was for sale looked like:

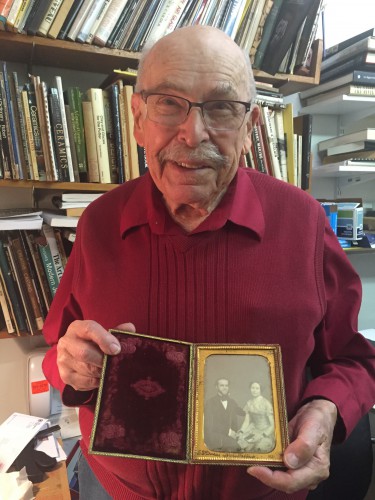

Nevertheless, the condition of the plate did not turn me off. That is because, by coincidence, just days earlier, I had visited with Julian Wolff, a friend. Julian is a World War II veteran who I have known for decades. We met years ago at a show of antique photographs–over the years Julian set up as a dealer at many shows I attended as a collector. We became friends, and I learned that he was also a very talented glass artist. When I visited with Julian, by coincidence, just days before seeing the image above for sale, he told me of his love for buying damaged daguerreotypes–at bargain prices–and then using his skill and experience to clean them up.

So, as I thought about bidding on this photograph of the Darlings, it occurred to me that we might be able to get Julian to clean this plate up.

Ultimately, I was successful in buying this cased photograph for The Green-Wood Historic Funds Collections. So, while I waited to receive it, I contacted Julian and asked him if we might hire him to clean it. Julian–wonderful person that he is–said he would be happy to work on it–but that, because he enjoyed the challenge so much, he would do it for free! He explained: “I love to find a daguerreotype that is so disfigured by tarnish and dust that one can hardly see the image. 150 years can do that to a silver surface. I get such pleasure to be able to see what had been hidden underneath the accumulated dirt, dust and tarnish of all that time and to see what S. E. Darling and his wife Margaret saw those many years ago.”

So we received the dag at Green-Wood and sent if off to Julian. Here’s what he saw:

. . . numerous scratches and rubs over most of the plate. There were many tiny pinpricks in the silver surface and there were large areas of tarnish scattered over the plate and an area on lower half of the woman that looked to have problems with the silver surface, looked somewhat etched. A mess.

And here’s how Julian described the cleaning process:

I removed the protector and mat and cover glass.

The image had been unsealed at some point. I placed the image in distilled water for a few minutes to remove any surface dust.

Next, a few seconds in a cleaning solution as the discoloration disappeared and then quickly back into distilled water to wash off the cleaner. Then I sprayed the image with a water pick to try to remove any residual cleaner that may have been stuck in some of the pits and scratches. I blew off the water from the surface with an air pump. Having cut new glass to replace the original I assembled the image with the original mat and new glass and sealed the image with Filmoplast P90 archival tape and surrounded the package with the original preserver. I repaired the case that had loose rails and reglued the loose hinge. The daguerreotype looked wonderful !

Julian noted: “Tarnish can be removed. Scratches, rubs and pits cannot.”

Now it was up to me to establish that my preliminary conclusion, that the Darlings, Samuel and Margaret, husband and wife, are in fact interred at Green-Wood. First step was to pull their index cards–the information about them obtained at the time of their burial–that are kept in Green-Wood’s Administrative Office. In theory, each person interred at Green-Wood–all 570,000 of them–has an index card. The reality, however, is a bit different. Index cards are occasionally filed in the wrong place. Or they may disappear, one way or another. In any event, there was indeed an index card for Margaret Darling. As per that card, she was born in the United States, was 64 years old when she died on August 2, 1881 (and therefore was likely born in 1817). Her address at the time of her death was 223 East 30th Street in Manhattan. Her cause of death was “heart.” She is listed as a widow.

We found just one index card for a Samuel Darling. He was indeed interred in the same lot as Margaret: 4976. He died on January 13, 1874. But his address was listed as 671 Clermont Avenue in Brooklyn–not Margaret’s address when she died. There were, however, two bigger problems: he was 91 years old and himself a widower when he died. Margaret and Samuel could not have been married if he was a widower and she was a widow. Now look at the daguerreotype–this Samuel would have been almost 70 years old when the photograph was taken circa 1850; the man in the photograph clearly is not that old. Further, I found a family tree online for this Samuel–his wife’s name was Nancy, not Margaret. So he is not the Samuel Darling in the photograph.

But we still had another possibility: there was a second Samuel Darling who was interred, as we discovered from the burial inquiry database, in lot 4976 in 1854–though there was no index card for him. Perhaps he was the Samuel Darling who had been Margaret’s husband. Checking the lot card that listed everyone interred in that lot, I confirmed that a second Samuel Darling was interred in lot 4976 on December 21, 1858. I then checked Green-Wood’s chronological books, which list every burial from the first burial in 1840 through those in 1937–and are the source for the information that goes on the index cards. There, listed as having been interred on December 21, 1858, were 5 Darlings, including a Samuel; all had been removed from their first place of burial place in Manhattan–likely a church yard in the lower part of the island that had been sold off for commercial development. Because Samuel was a removal, we did not have any more information on him–not his age at death, not his date of death, not his last address, and not his marital status. But, researching Margaret further, I found that a Margaret Darling who was listed for more than a decade in the New York City directories–from 1867 through 1880–as the widow of Samuel and living at 223 East 30th Street in Manhattan. This established that the Margaret Darling who is interred at Green-Wood–223 East 30th was also her address–had been married to a Samuel Darling and that he died before 1867, leaving her widowed.

My educated guess? This photograph, judging from its appearance, the clothes, the case, etc., was taken about 1850. Indeed, the writing at the bottom of the mat dates the image as “1851.” We know that Samuel and Margaret Darling married in 1851–I found a record online of that marriage. If, as per Green-Wood’s records, the Margaret Darling interred there likely was born in 1817, she would have been 34 years old in 1851, when she married. And that, indeed, matches up well to the appearance of the woman in the photograph. Given that Samuel and Margaret seem to be wearing their best as they posed for the daguerreotype, my guess is that they splurged on what was still a big expense at the time–to have their photograph taken contemporaneously with their marriage. So, I believe that the individuals in this daguerreotype, identified as Samuel and Margaret Darling, are the same Samuel and Margaret Darling who are interred at Green-Wood in lot 4976.

Convinced, as a cemetery historian, that an important, but often overlooked, story of an individual’s life is his or her final resting place, I went out to section 8 at Green-Wood to find lot 4976. It turns out that it is right next to the grave of the famous Lola Montez, the “Spanish Dancer” who was a worldwide sensation, one of the most famous people of the 19th century. Google her for her incredible story! Unfortunately, neither Samuel nor Margaret has a visible gravestone. Perhaps markers are there, in the ground or unreadable after a century and a half of exposure to the elements. But I could not find them. Here’s the lot:

The Darlings lie anonymously at Green-Wood, their graves unmarked. But now we can see their faces and begin to understand the lives that they lived.

Great thanks to Julian’s lovely daughter, Judy, for photographically documenting her father’s cleaning process and sharing her photographs of it.

A great story about this tin type