One hundred and fifty years ago, in April, 1861, war fever was sweeping New York City.

In the wake of the bombardment of the Union garrison at Fort Sumter, in Charleston Harbor, South Carolina, Major Robert Anderson and his men were transported by ship to New York City. They arrive to a hero’s reception on April 18.

In the meantime, great excitement swept New York City. George Templeton Strong, the great New York City diarist, wrote:

April 15. Events multiply. The President is out with a proclamation calling for 75,000 volunteers and an extra session of Congress July 4. It is said 200,000 more will be called within a few days. Every man of them will be wanted before this game is lost and won. Change in public feeling marked, and a thing to thank God for. We begin to look like a United North. Willy Duncan (!) says it may be necessary to hang Lincoln and Seward and Greeley hereafter, but our present duty is to sustain Government and Law, and give the South a lesson. The New York Herald is in equilibrio today, just at the turning point. Tomorrow it will denounce Jefferson Davis as it denounced Lincoln a week ago. The Express is half traitorous and half in favor of energetic action against traitors. The Journal of Commerce and the little Day-Book show no signs of reformation yet, but though they are contemptible and without material influence for evil, the growing excitement against their treasonable talk will soon make them more cautious in its utterance. The Herald office has already been threatened with attack. Mayor Wood out with a “proclamation.” He must still be talking. It is brief and commonplace, but winds up with a recommendation to everybody to obey the laws of the land. This is significant. The cunning scoundrel sees which way the cat is jumping and puts himself right on the record in a vague general way, giving the least possible offence to his allies of the Southern Democracy. The Courier of this morning devotes its leading article to a ferocious assault on Major Anderson as a traitor beyond Twiggs, and declares that he has been in collusion with the Charleston people all the time. This is wrong and bad. It is premature, at least …

April 16. A fine storm of wind and rain all day. The conversion of the New York Herald is complete. It rejoices that rebellion is to be put down and is delighted with Civil War, because it will so stimulate the business of New York, and all this is what “we” (the Herald, to wit) have been vainly preaching for months. The impudence of old J. G. Bennett’s is too vast to be appreciated at once. You must look at it and meditate over it for some time (as at Niagara and St. Peter’s) before you can take in its immensity. His capitulation is set-off against the loss of Sumter. He’s a discreditable ally for the North, but when you see a rat leaving the enemy’s ship for your own, you overlook the offensiveness of the vermin for the sake of what is movement indicates. This brazen old scoundrel was hooted up Fulton Street yesterday afternoon by a mob, and the police interfered to prevent it from sacking his printing office. Though converted, one can hardly call him penitent. St. Paul did not call himself the Chief of the Apostles and brag of having been a Christian from the first. This and other papers say the new war policy will strangle secession in the Border States. But it seems to me that every indication from Virginia, North Carolina, and elsewhere points the other way. No news from Slave-ownia today, but most gladdening reports from North, West, and East of unanimity and resolution and earnestness. We are aroused at last, and I trust we shall not relapse into apathy. . . . Thence to New York Club. Our talk was of war. Subscribed to a fund for equipment of the Twelfth Regiment and put down my name for a projected Rifle Corps, but I fear my near-sightedness is a grave objection to my adopting that arm. I hear that Major Burnside has surrendered his treasurership of the Illinois Central Railroad and posted down to Rhode Island to assume command of volunteers from that state. Telegram that 2,500 Massachusetts volunteers are quartered in Faneuil Hall, awaiting orders. GOD SAVE THE UNION, AND CONFOUND ITS ENEMIES. AMEN.

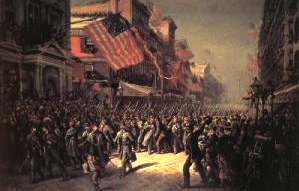

On April 19, the famed Seventh Regiment, New York State Militia, marched down Broadway, to the cheers of thousands, including Major Robert Anderson, who reviewed the troops from the balcony of Ball & Black Jewelry Company (565 Broadway, now Victoria’s Secret Soho), at the southwest corner of Broadway and Prince Street. According to the report that would appear in the Third Annual Report of the Bureau of Military Statistics of the State of New York, published in 1866,

New Yorkers cheered and applauded as the Silk Stocking Regiment marched through the city. The line of march was a perfect ovation. Thousands upon thousands lined the sidewalks. It will be remembered as long as any of those who witnessed it live to talk of it, and beyond that it will pass into the recorded history of this fearful struggle. . . . The regiment marched not as on festival days – not as on the reception of the Prince of Wales – but nobly and sternly, as men who were going to the war. Hurried was their step – not as regular as on less important occasions. We saw women – we saw men shed tears as they passed. Amidst the deafening cheers that rose, we heard cries of ‘God bless them!’ And so along Broadway and through Cortland street, under its almost countless flags, the gallant Seventh regiment left the city.

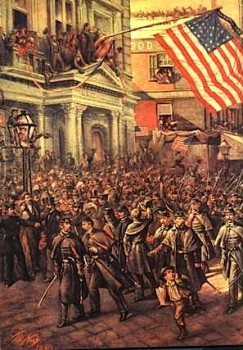

The next day, April 20, a massive meeting was held in Union Square. The crowd, estimated at 100,000, the largest that had ever gathered in the history of the nation until then, roared its approval as several of the heroic soldiers who had garrisoned Fort Sumter were introduced and patriotic speeches were made. Though sentiment was far from unanimous, the movement towards war with the secessionist states gained momentum. Here’s the New York Times’ lead for its story the next day, dramatically headlined “THE UNION FOREVER!; Immense Demonstration in this City. THE ENTIRE POPULATION IN THE STREETS:”

The Empire City, yesterday, spoke in tones of thunder for the Union, the Constitution and the enforcement of the laws. The largest meeting, without exception, that was ever held on this continent, and the most enthusiastic,

was that which came together at Union-square and in the vicinity yesterday — for the hundred thousand and unnumbered thousands more who responded to the call were too numerous to find standing room within the limits of the Square itself. Into the adjoining thoroughfares the crowds overflowed, and

- Broadway from Fourteenth-street almost to the Battery was a surging mass of human beings all the afternoon. The stores were closed, and everywhere, on house-tops and mastheads, and on men’s hats and next their hearts, and even in ladies bonnets were the Stars and Stripes, — the emblem of a Union which the people have declared “must and shall be preserved.” They who of late, and not without some show of reason, have upbraided Americans for the seeming apathy with which they first heard how that flag had been dishonored, should have seen the demonstration of yesterday. Union-square was a red, white and blue wonder. Countless little flags were hung from windows or waved by ladies and children who looked forth from them. Not only the adjacent hotels, — the Clarendon, the Everett. the Union Place, the Monument House, — displayed national colors in profusion, but from nearly every private house, from Spingler Institute and from the Church of the Puritans, the flag of our Union waved proudly.

In April, 1861, war fever did indeed sweep New York City.

Note: Several of Green-Wood’s permanent residents are mentioned above. Greeley is, of course, Horace Greeley, editor of the New York Tribune and then one of the leading shapers of opinion in America. J.G. Bennett is James Gordon Bennett, editor of the New York Herald, the most powerful newspaper in America, who, despite his racist leanings, was heavily courted by President Abraham Lincoln, in need of Bennett’s support for the war. The other great New York City editor of the time, Henry J. Raymond of The New York Times, a Republican who was close to Lincoln, delivered a patriotic speech at the Union Square rally. And the band that played the martial tunes at the Great Union Meeting was none other than Dodsworth’s–led by Harvey Dodsworth, who also is interred at Green-Wood.