Use the box here to search across all of our short biography collections for veterans.

You can also search our full database of burials or try the sitewide search in the navigation bar at the top of this page.

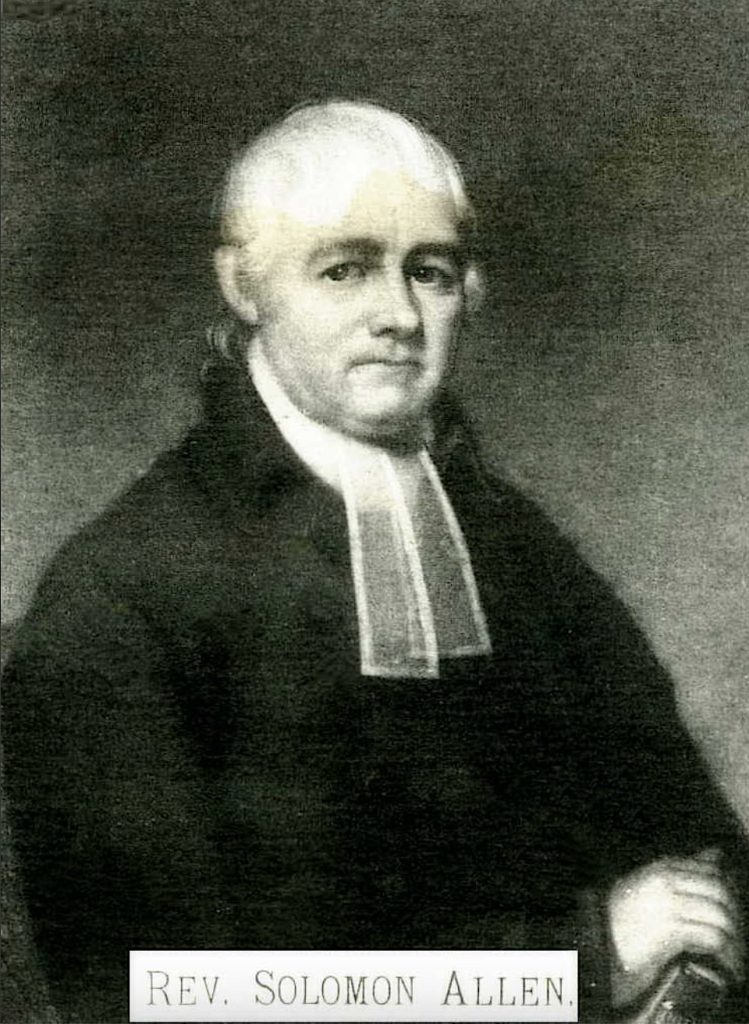

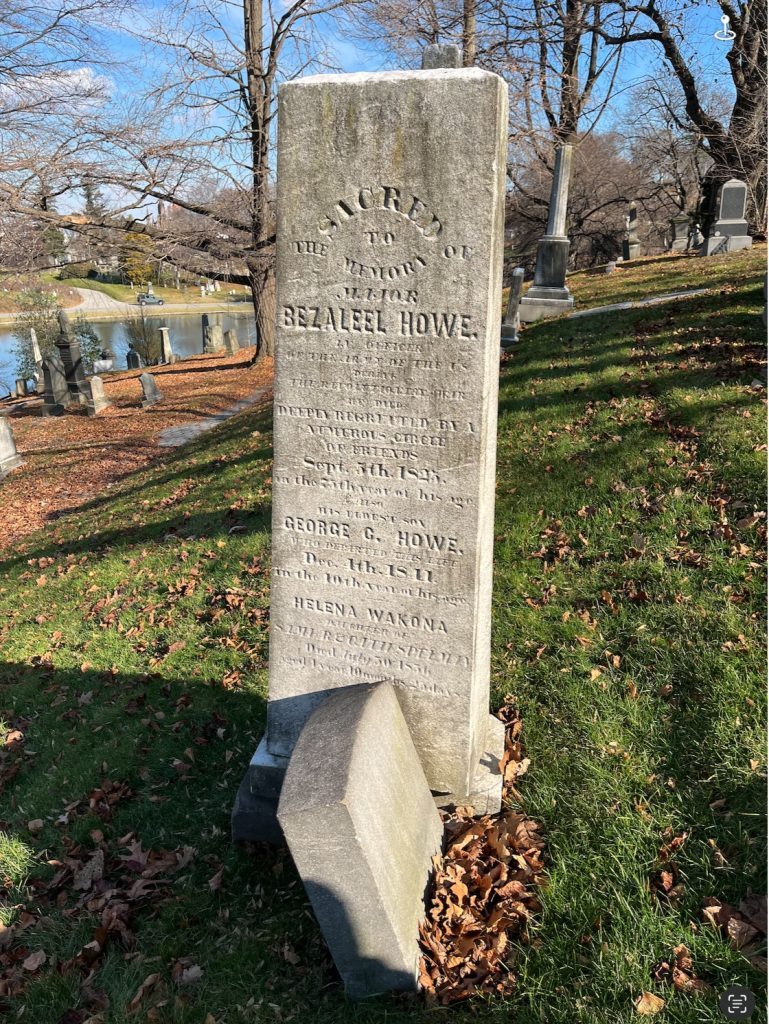

ALLEN, SOLOMON (1751-1821). Major, Berkshire Militia, Continental Army. As per a biographical sketch of Solomon Allen, published in Biographies of Monroe County People, “Lest We Forget” (Massachusetts, November 19, 1910), he was born in Northampton, Massachusetts, in January of 1751. According to an Ancestry.com online family tree, his parents were Joseph and Elizabeth née Parsons Allen. The Sons of Liberty website names his spouse as Beulah Clapp; their son was named Moses (born 1789); the aforementioned family tree names another son, Phineas (born 1776), and dates his marriage as August 15, 1771.

Wikipedia and Appletons’ Cyclopededia of American Biography document that his brothers, Moses and Thomas, were chaplains in the Army during the Revolutionary War. Solomon, as a soldier in the Continental Army, rose to the rank of major. Earlier, while serving as a lieutenant, he was involved in the investigation of General Benedict Arnold’s treason. He served in the guard that took British Major John André, Benedict Arnold’s intermediary, to West Point where Arnold had his headquarters. Washington’s Spies, The Story of America’s First Spy Ring by Alexander Rose confirms that Lieutenant Allen, on September 22, 1780, was responsible for transporting the papers that André was carrying, proving Arnold’s treason, to General George Washington, rather than delivering them to Arnold. The Sons of the American Revolution website states that Allen was a 2nd major in Colonel Israel Chapin’s 2nd Hampshire County Regiment in an unstated year.

“Lest We Forget,” the biographical sketch of Solomon Allen, reports that he and four of his brothers served in the War of Independence. It notes that he arrived in Cambridge on August 15, 1777, when a group of American Indians attacked a party of Americans there. Allen was serving with others from the Berkshire Militia. He was described of having “bellicose ardor of the most glowing kind.” His men, eager to fight, soon engaged at the Battle of Bennington. After the war, he was a participant in the suppression of Shay’s Rebellion.

Further details of Allen’s military service appear in Massachusetts, U.S. Soldiers in the Revolutionary War. Initially, Solomon was a private from Northampton in Captain Jonathan Allen’s Company, General Pomeroy’s Regiment, which marched on April 20, 1775, in response to the alarm of the previous day; the unit remained active for 15 days and returned home on May 4, 1775. He then enlisted from Gloucester as a private on February 9, 1776, in Captain Abraham Dodge’s Company, Colonel Moses Little’s 12th Regiment, and was on the muster roll on April 24, 1776. On June 22, 1777, Allen received a certificate of service from Colonel Thomas Crafts, stating that he was employed in the laboratory one month after his regiment disbanded and was paid for that service. Subsequently, he served for eight days in late September 1777 during which time he marched to Stillwater and Saratoga. He re-enlisted on July 4, 1780, was a third lieutenant under Captain Ebenezer Sheldon, Colonel Seth Murray’s Regiment, served for three months and fourteen days, and was discharged on October 10, 1780. (This was the period during which Benedict Arnold committed treason.) That company was raised to reinforce the Continental Army.

Two of Allen’s great-great grandsons applied for membership in the Sons of the American Revolution: Clarence Breedlove Clarke, who was born in Indianapolis, and Theodore Usher Cone, who was born in Minneapolis. Their very detailed applications rely upon the service noted in the Massachusetts records.

The 1790 census reports that Allen lived in Pittsfield (Chesterfield), Massachusetts; his household included four free white males (one over 16) and four free white females, no names or relationships given. In 1791, at age 40, he became a religious convert and was working as an itinerant preacher 10 years later. His sketch in “Lest We Forget” reports that was aided by Dr. Timothy Dwight, the president of Yale, who supported his efforts to enter the ministry in which Allen was licensed at age 53. In 1800, the census shows him living in Northampton; seven free white persons lived in his residence.

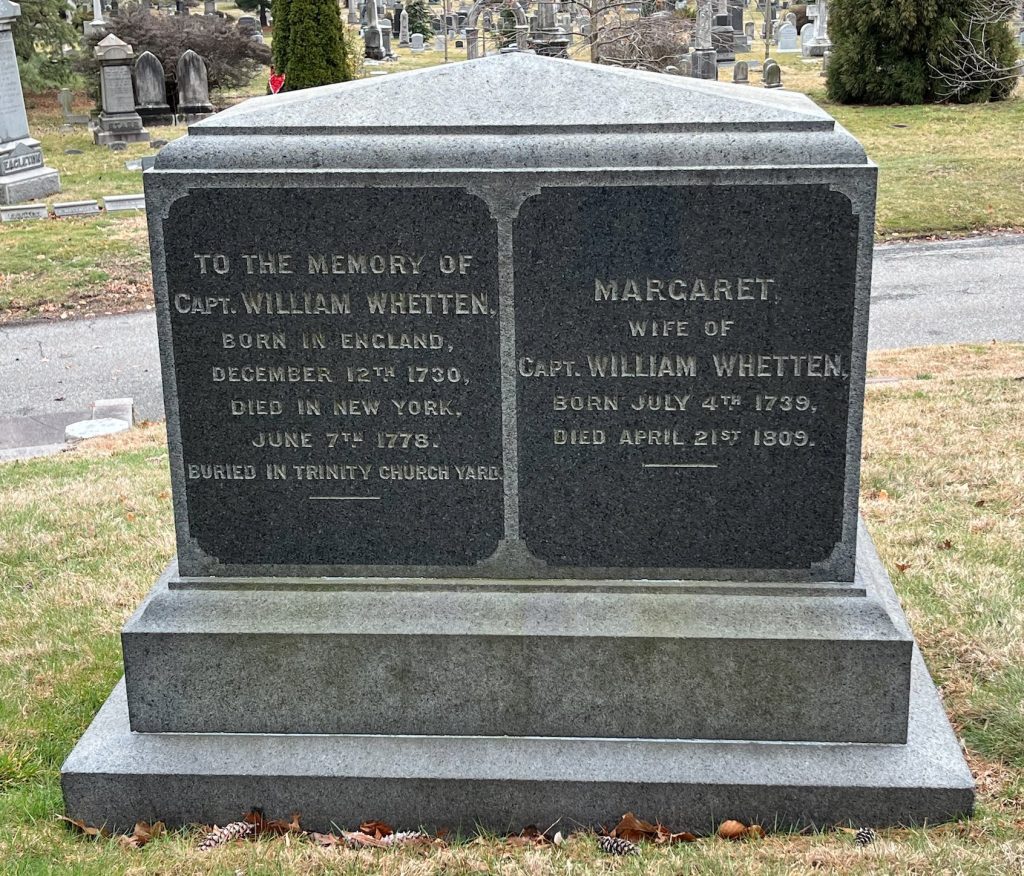

His mission took him to western New York where his religious zeal earned great respect. He received no money for his missions but established four churches and the first Sunday school in rural New York. Much of his ministry was in Brighton, New York, near Rochester. He was reportedly loved for his kindness and ability to administer comfort to those in need. The 1820 census documents his residence as Berkshire, Massachusetts. He died at the home of his son Moses in New York City on January 19, 1821. On October 10, 1822, the Pittsfield Sun reported that it had published Last Hours of Rev. Solomon Allen which was for sale for 20 cents. Proceeds from the publication would be donated to the Berkshire Bible Society. Green-Wood’s Chronological Records note that Solomon Allen and six other family members were removed from their interment in New York City to Green-Wood Cemetery on May 22, 1856; all are buried in the same lot. Those removed with him include his sons William E. and Theodore as well as a Priscilla Paddock (Paddock, as per the Sons of the American Revolution application of descendant Theodore Usher Cone, was a family name). Moses Allen, his son, was interred upon his death in 1877 in that same lot. Section 60, lot 991.

AMERMAN, SR., ALBERT CLAYTON (1733-1814). Private, Somerset County Militia, New Jersey. Genealogical records show that Albert Clayton Amerman, Sr. was born on February 8, 1733, in Harlington (Harlingen) or Sowerlands (Sourland), Somerset County, New Jersey. Of Dutch ancestry, Albert’s parents, according to Ancestry.com records, were Pouwel Paulus Albertse Amerman and Alida Reyniersen van Hengemlen. The surname was alternately spelled as “Ammerman,” and Albert’s father’s first name was also recorded as Derick or Dirck, while his mother was also known as Helena, per genealogical records from Geni, a social networking website. He had a sister, Helena Dodge.

Albert’s date of baptism, in the Dutch Reformed Church at Readington, New Jersey, is posted on Ancestry.com, perhaps from a family history, as July 8, 1733. Much of the information we have on Albert was passed down through family histories and may not be as reliable as government records.

When Albert was three years old, Ancestry.com reveals from a probable family history, his family moved from Sowerlands to New York City. After becoming a baker’s apprentice about 1748, Albert went into the baking business when he came of age but, after a short time, he became engaged in building light, flat-bottomed boats, termed “bateaux,” for the transportation of provisions for the British Army during the French and Indian War. About four months later, he went to Cold Springs and baked for the Jamaica and Halifax fleet.

It appears that Albert may have been married twice. There are many discrepancies involving marriage records. His first wife may have been Maria or Marya Wyckoff. Albert’s name was recorded as Elbert in Dutch Reformed Church records and the marriage took place on December 9, 1758, in New York City. William (Bill) Morgan Amerman, Albert’s first cousin, four times removed, wrote, on June 19, 2006, that the bride’s name was also recorded as Prudence (although this may have been a reference to Appolonia, who was definitely married to Albert.) Appolonia or Apolonia de la Montagne or Montanye, daughter of Thomas de la Montaigne and Rebecca Bryan, and Albert may have married in 1774 in Bedminster, Somerset, New Jersey. Family histories show she was born on either August 9, 1741, or September 3, 1741, and that she was also from Sourland.

Birth documents show that Albert had at least one child with spouse Marya, named Isack (Isaac.) According to several genealogical records, Albert had at least 11 children, and as many as 15, including one named Albert Clayton Amerman, Jr. Unfortunately, these records regarding his children are also unreliable, especially regarding their birth years.

Continuing as a baker in New York City, Albert was then employed as a cartman when the Revolutionary War began. In 1776, once the British occupied the city, Albert moved with his family to New Hackensack, Dutchess County, New York. For the next five years of the war, he baked for the American Army.

As documented in William Stryker’s Official Register of the Officers and Men of New Jersey in the Revolutionary War, 1872, Albert was a private in Captain Vroom’s Company, 2nd Battalion, Somerset County Militia, New Jersey, as well as in Captain Jacob Ten Eyck’s Company, 1st Battalion, Somerset County Militia. According to Albert’s cousin, Albert baked in a village north of Poughkeepsie, New York, until the British, having taken Fort Montgomery, destroyed the village. He then baked for the invalids of New Hackensack. Once the British evacuated New York City at the close of the war, Albert and his family returned, and he resumed his carting business.

The 1790 United States federal census shows Albert Amerman living in what was the Montgomery Ward section of New York City, now part of downtown Manhattan. There were eight household members, of which two were free white males aged 16 and over, three white males under 16, and three free females.

The 1800 federal census shows Albert Amerman living in Ward 5, New York City, with two household members in all: a free white male of 45 or over and a free white female of 45 or over. However, the 1810 federal census shows 10 household members, living in Ward 5, with one male 45 and over and one female 45 and over. There were three household members under 16 and all residents were white and not enslaved.

It does appear that Albert owned land and may have lived in New Jersey. In February 1794, a petition seeking construction of a road in Hardwick Township, New Jersey, “through Albert Amerman’s farm,” was filed with the Sussex County Court of Common Pleas and Quarter Sessions. And in the Abstracts of Wills, New Jersey, 1814-1817, he is listed, on February 5, 1814, as “of Montgomery Township, Somerset County.”

When Albert was 64 or 65 years old, an injury forced him to retire. Though various records report several different dates of death for him, his will was probated in early 1814, his likely year of death. An inventory of his possessions at that time included an “English bible” and half a pew in the Harlingen Church. Initially interred at the Dutch Middle Church, his remains were removed from there to Green-Wood, where he was reinterred on December 24, 1857, according to cemetery records. His wife, Appolonia Amerman, died on August 23, 1815, and was reinterred in Green-Wood on the same day as her husband. Section 69, lot 4569.

BENSON, ROBERT (1739-1823). Lieutenant colonel and aide-de-camp, Cantine’s Regiment, New York Militia, Continental Army. An online family tree cites Robert’s birth in New York City. As per records in the Center for Brooklyn History, Guide to Robert Benson Deeds, Benson’s family lineage dates to great-great grandparents who immigrated from Amsterdam, The Netherlands, to New York City in 1648. Benson’s father, Robert (1715-1762), a brewer on Cherry Street in what is now lower Manhattan, married Catherine Van Borsum (1718-1794) in 1738. They had six children, two daughters, Mary and Cornelia, who died young, and four sons, Robert, Henry, Egbert and Anthony. All four young men served in the American Revolution and were members of the Sons of Liberty. Robert’s parents are listed in Dutch Reformed Church Membership Records.

In 1762, Robert inherited his father’s brewery and worked as a brewer, but eventually sold the property. As per an online biography of the Benson family, Robert was an assistant alderman from 1766 to 1768. In 1770, Robert’s mother sold the property on Cherry Street and moved to Maiden Lane, corner of William Street, where they had a house and adjoining lot, and where they lived until the start of the American Revolution. Their mother relocated to Dutchess County during the war for her safety, the house was abandoned, and it was later occupied by the British. This property was ultimately inherited by Robert.

As per his wife’s pension record, Robert entered service on September 15, 1775, as a member of Cantine’s Regiment, New York Militia, was commissioned as a first lieutenant in the New York troops and served as aide-de-camp and military secretary to Governor George Clinton. By the end of the war, he held the rank of lieutenant colonel. He was with Clinton and General George Washington when the British evacuated New York City on November 25, 1783. Information on the Sons of the American Revolution website also notes that he was an aide-de-camp to Governor George Clinton during the war; that website reports that knowledge of his service was provided by volunteer researchers, not descendants. His position as aide-de-camp to Clinton is further confirmed by notes in the Guide to Robert Benson Deeds. In addition, Robert served as a member of the first Committee of Safety and was secretary of the Provincial Congress of New York in 1776. This information is also noted in the application of Egbert Benson, great-grandson of Robert, in his application to be a member of the Empire State Society, Sons of the American Revolution. Egbert notes Robert Benson’s involvement as a “partisan in the cause” and his membership in conventions until the State was organized under the Constitution, at which time Robert was chosen as secretary of the State Senate.

Following the American Revolution, the aforementioned guide documents that Robert acquired farmland in Brooklyn and bought and sold properties there. Benson held deeds to property in the Brooklyn Heights neighborhood dated in 1795, 1801, 1802, and 1804. The 1801 deed was transcribed by Washington Irving for land on Joralemon Street; the 1804 deed was from Benson to Pierpont (Pierrepont). The Brooklyn neighborhood of Bensonhurst bears the family name. Benson’s brother, Egbert, was appointed as the first attorney general of New York State in 1777 and was one of the founders and the first president of the New-York Historical Society. The 1816 New York Jury Census notes that Benson was living on Broadway in New York City and that his occupation was “gentleman.”

According to his widow’s pension application, he married Dinah Cowenhoven in Brooklyn on March 27, 1785; the officiant was Reverend Martinus Schoonmaker, pastor of the Reformed Dutch Church there. The pension application was executed on June 17, 1838, pursuant to an act of Congress that gave half-pay and pensions to certain widows. Dinah Benson, then seventy-seven years old, declared that Robert was a lieutenant in the militia at the start of the war, then was appointed aide-de-camp in 1777, serving throughout the conflict. She noted that she only knew him as holding the rank of colonel. That application names their children: Maria, their third daughter (born January 5, 1793) and Jane, their fourth daughter, born March 13, 1794. His widow attested that Robert Benson died in New York City on February 25, 1823. Benson’s online family tree names six children who were older than the two girls named in the pension application, four sons and two daughters. However, North American Family Histories for Robert Benson reports that there were eight children, one of whom, Jane, the youngest, married Dr. Richard Kissa Hoffman in 1822.

Robert Benson’s remains were removed from an unnamed cemetery in New York and re-interred at Green-Wood on May 21, 1875. As per Find A Grave, the inscription on a bronze tablet that was formerly at his grave notes that he was the aide-de-camp to Governor George Clinton during the American Revolution, clerk of the New York State Senate and clerk of the New York Common Council. The aforementioned plaque was placed by Philip A. Benson, Arthur D. Benson and John C. Lowe (relationships unstated) in 1939. Section 28, lot 10776.

BERGEN, SIMON (1746-1777). First lieutenant, Brooklyn, New York Militia. Born in Gowanus, Brooklyn, on October 13, 1746, according to Daughters of the American Revolution records, Simon Bergen’s ancestry can be traced to Hans Hansen Bergen, a ship-carpenter who was a native of Bergen, Norway, and later settled in Holland. From there, in 1633, he immigrated to New Amsterdam, now New York City, becoming one of the area’s earliest Dutch settlers. Simon’s father, Johannes Bergen (1721-1786), married Catryntie (or Tryntje) De Hart (or DeHart) and thus, per a report by the New York City Cemetery Project, the 300-acre DeHart farm near Gowanus Bay came to be owned by the Bergen family. Built in the 1670s and demolished in 1891, the DeHart-Bergen stone house stood west of Third Avenue near 37th and 38th Streets, overlooking Gowanus Bay. As reported in The Bergen Family, Descendants of Haus Hansen Bergen, One of the Early Settlers of New York and Brooklyn, Long Island, the land was part of a tract of 930 acres “purchased” by William Arianse Bennet and Jaques Bentin from Native Americans in 1636.

As related by The Bergen Family, Simon Bergen also married a DeHart. Gashe DeHart was born on February 4, 1744, and the couple’s marriage in Monmouth County, New Jersey, was recorded on May 18, 1767, per Dutch Reformed Church Records 1639-1989. Their son, also named Simon, was born on April 15, 1768, as noted in North American Family Histories 1500-2000.

By March, 1776, Simon held the office of lieutenant in Captain Lambert Suydam’s Kings County Troop of Horse, “organized by the Provincial Congress for revolutionary purposes” per a Sons of the American Revolution membership application, 1889-1970, completed by a descendent, Schuyler Bergen Jr. Simon is listed as holding the rank of first lieutenant in that militia unit, according to Frederic Gregory Mather’s The Refugees of 1776 from Long Island to Connecticut, 1913.

As carved on his headstone at Green-Wood and reported in the records of both the Daughters of the American Revolution and Sons of the American Revolution, Simon died on February 22, 1777. While in the process of buying a musket, the firearm went off accidentally and shattered Simon’s legs. The March 3, 1777, edition of the Gaines’s New York Gazette and Mercury reported that Simon died from a loss of blood before help could arrive. The accident was reported to have occurred in front of the old DeHart-Bergen house where he lived.

Three months after Simon died, his second son, John S. Bergen, was born on May 1, 1777, as reported in North American Family Histories 1500-2000. Gashe Bergen, Simon’s wife, died on March 18, 1781, as carved on her headstone and stated in Sons of the American Revolution records.

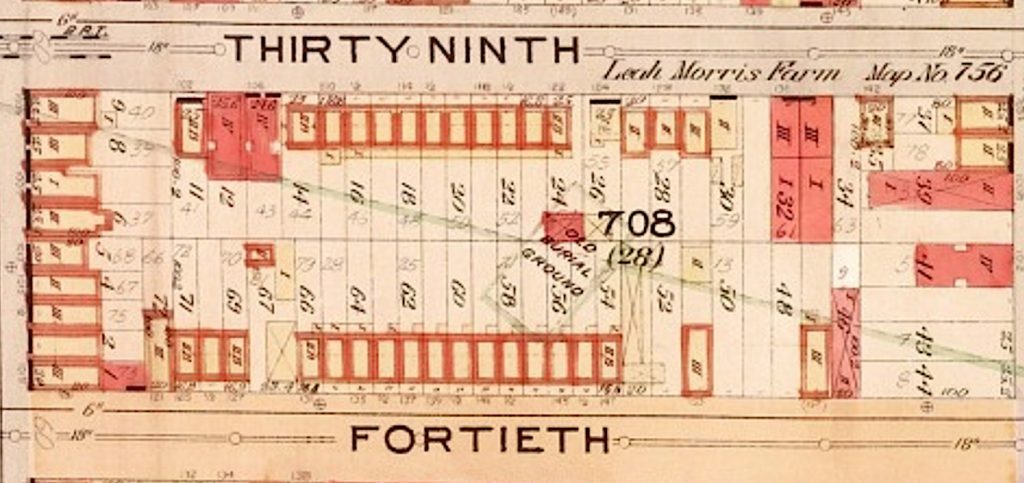

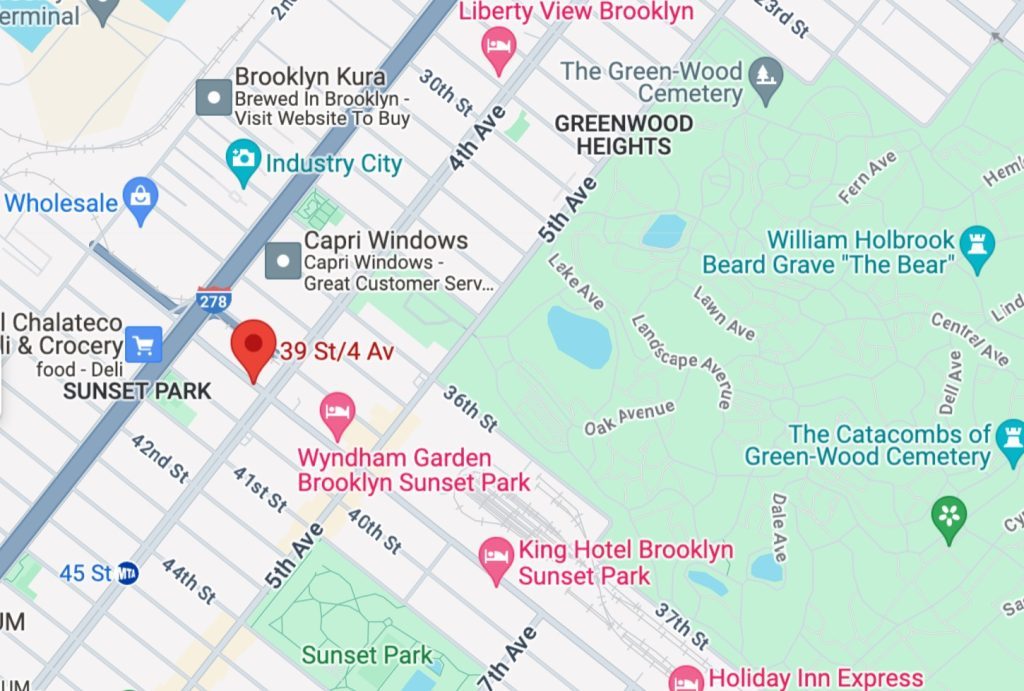

The Bergen family burial ground in Gowanus, surrounded by a stone wall, was situated just east of the ancient DeHart-Bergen House, in the middle of the block bounded by 39th and 40th Streets and Third and Fourth Avenues. On December 16, 1848, per Green-Wood Cemetery records, Simon and his wife Gashe’s remains were removed from this homestead burial ground to nearby Green-Wood for re-interment, along with the remains of four of their son John’s ten children: Gashe, Michael, Mary Gashe, and Simon J. Bergen. Simon J. Bergen was the only one of the four grandchildren to have lived to adulthood. John S. Bergen, his wife, Maria T. Hubbard Bergen, and their other children are also interred in Green-Wood. Section 61, lot 1226.

BIRD, MATTHEW WILLIAM (1756-1816). Soldier, Massachusetts Artillery, Continental Army. According to the Record of Birth in Dorchester, Massachusetts, Matthew was born on January 7, 1756, in that town, to Elinor and Matthew Bird. He was baptized at the First Church of Dorchester eleven days later. Matthew is a descendant of the Thomas Bird who sailed from England on the second voyage of Mary and John in 1635. Thomas Bird settled and built a homestead in Dorchester. As per the Dorchester Atheneum Museum, “By 1931 ten generations of his descendants had lived here. The house, which was located at 41 Humphreys Street, was known also as the Bird-Sawyer House.” Unfortunately, the house was demolished during the late 1900s. According to the Dorchester Historical Society:

The Thomas Bird who built the house made his money from tanning, and even in the early 20th century, there were people who remembered traces of the tanning canals nearby. It was under Corp. Thomas Bird, fifth owner, that the house played its proudest part. Aged 21 when he inherited, young Thomas had fought in the Concord and Lexington engagement and at Bunker Hill, when coming home one evening early in March, 1776, from guard duty at Boston Neck, he found himself outranked in his own house. Col. Gridley of the American engineers was quartered there with his staff—Putnam, Waters, Baldwin and [Henry] Knox, later to become the famous general.

The house was ideal for use as a headquarters. Its large upper chambers were used as draughting (drafting) rooms for drawing up the fortification plan for Dorchester Heights, a hill that was within a short walking distance. Washington rode over from Cambridge to direct the work, and when the thousands of bundles of birch and elder fascines for the ramparts were carried to the Heights, they passed down the lane in front of the house.

As per Heroic Willards of ’76, a family genealogy compiled by James Andrew Phelps and published in 1917 (note that Sarah Willard, 1789-1873, married Matthew William Bird, the son of Mary and the subject of this biography, Matthew William Bird), Matthew Bird “enlisted May 3, 1775, under Captain Thomas W. Foster in Colonel W. Gridley’s Regiment Massachusetts Artillery; serving therein at the siege of Boston.” An excerpt from the History website documents that siege:

From April 1775 to March 1776, in the opening stage of the American Revolutionary War (1775-83), colonial militiamen, who later became part of the Continental army, successfully laid siege to British-held Boston, Massachusetts. The siege included the June 1775 Battle of Bunker Hill, in which the British defeated an inexperienced colonial force that nevertheless managed to inflict heavy casualties. In July 1775, General George Washington arrived in the Boston area to take charge of the newly established Continental army. In early March 1776, Washington’s men fortified Dorchester Heights, an elevated position just outside of Boston. Realizing Boston was indefensible to the American positions, the British evacuated the town on March 17 and the siege came to an end.

Heroic Willards of ’76 further reports: “That (Matthew Bird’s) enlistment terminated January 1, 1776, when he re-enlisted in the regiment of Colonel Henry Knox; being subsequently at the battle of Long Island . . . .” A second tour of duty for Matthew and a second major battle. The website on the 1776 Battle of Long-Island details:

The Battle of Long Island (aka Battle of Brooklyn and the Battle of Brooklyn Heights) was the first major battle of the war to take place after the United States declared its independence on July 4, 1776. It was a victory for the British and the beginning of a successful campaign that gave them control of the strategically important city of New York. In terms of troop deployment and fighting, it was the largest battle of the entire war.

The Continental Army did not fare as well in the Battle of Brooklyn as it had during the siege of Boston. George Washington and his troops were driven out of Brooklyn, then New York entirely, and retreated to New Jersey and Pennsylvania. According to the History website, “the Americans suffered 1,000 casualties to the British loss of only 400 men.”

During this battle, 1,100 Americans were captured. Sadly, Matthew was one of those captured; he was held as a prisoner in the old Rhinelander Sugar House at Duane and Rose Streets in New York City. Sugar houses were large buildings throughout the city that were used by the British as prisoner of war camps. The notorious brick Sugar House held up to 500 prisoners, both military men and those suspected of having helped the Patriot cause, who were subjected to beatings and starvation at the hands of the British.

On September 21, 1776, soon after Matthew Bird was imprisoned, New York City suffered a devastating fire. Dubbed “The Great New York Fire of 1776,” it destroyed over 600 buildings. As per Heroic Willards of ‘76, “After the great fire of September, 1776, the British tendered him a parole work in rebuilding the burnt district; which he accepted, and was still at it when they (the British) evacuated the city in 1783.” As per Some Account of the Cone Family: Principally of the Descendants of Daniel Cone, Matthew Bird married Mary Cone in 1778. According to the 1790 federal census, he was living in New York City with three females and two young males; as per the Bartholemew family tree on Ancestry.com, these were likely his wife Mary and their four children. Matthew passed away on January 11, 1816, as per newspaper reports.

On January 14, 1850, the remains of Matthew W. Bird, the subject of this biography, as well as those of three other members of his family (Mary Bird, identified in Heroic Willards of ‘76 as the name of Matthew Bird’s wife–she was born in 1750 and died on May 27, 1835; a second Matthew W. Bird, (the son of our subject), who lived 1783-1847; and a John Bird), were removed from the Carmine Street Churchyard in New York City and were interred at Green-Wood. Some gravestones were also removed, with the remains, to Green-Wood. The inscription on the gravestone of the son is still readable in raking light (illumination from an oblique angle). Section 82, lot 2668.

BLOOM, JACOB (?-1797). Second lieutenant, Kings County Militia, Light Horse Regiment. No documentation has been located as to the date and place of Jacob’s birth. According to Revolutionary Troops, Long Island, NY: The History of Long Island, from Its Earliest Settlement to the Present Time, as transcribed by Caralyn Brown, Jacob was one of several officers who had “signed the Declaration and taken their commissions, 1776.” He is listed as a second lieutenant in the Light Horse Regiment along with First Lieutenant William Boerum, Quarter Master Peter Wyckoff and others.

In Henry Stiles’s History of the City of Brooklyn (1867), he writes of the September 1776 British attack on Manhattan, and Jacob Bloom’s capture:

On the 15th occurred the occupation of New York Island by the British, which is thus described by Gen. Jeremiah Johnson, an eyewitness: “In the evening of the 14th,’ the Phoenix and Dutchess of Gordon frigates passed New York, with a large number of bateaux: the frigates anchored opposite Kip’s Bay,’ where the Rose joined them . . . . About 7 o’clock the ships opened a heavy fire of round and grape shot upon the shore, to scour off the enemy. The firing continued an hour and a half: when the leading boats passed the ships, the firing ceased. The boats passed to the shore, and all the troops landed in safety. We may be incorrect as to dates, but the facts are as stated. I saw the scene. It was a fine morning, and the spectacle was sublime. Thomas Skillman of Bushwick, and John Vandervoort, and Jacob Bloom, of Brooklyn, with their families, were at Kip’s Bay, in the house of Mr. Kip, when the cannonading of the three British frigates, which lay opposite the house, commenced. The cannon-balls were driven through the house. This induced them to take to the cellar for safety, where they were out of danger. After the landing the men were sent to prison in New York, and the next day their families returned to Long Island.

Stiles also relates that on April 13, 1775, Jacob purchased a farm from an Adrian Bogert. Jacob willed this homestead to his son, Barent who sold it to an Abraham A. Remsen in 1816. The farm would subsequently be sold to Abraham Boerum and would come to be known as the “Boerum farm.”

As per the 1790 federal census, a Jacob Bloome (sic) lived in Brooklyn, New York. His household was comprised of 16 members, including 9 enslaved people.

According to the New York Wills and Probate Records, 1659-1999, Jacob passed away in 1797 in New York City. His heirs were Maria and Barrent Bloom, son and daughter-in-law, and Jacob Bloom, grandson. His executors were Jeremiah Johnson, Peter G. Wykoff and David Springsteen. Both Johnson and Wykoff are mentioned in the historical pieces cited above.

As per Green-Wood’s chronological books, Jacob was buried in Wallabout Burial Grounds in Brooklyn and reinterred at Green-Wood Cemetery on June 16, 1851. Others who were removed from Wallabout and reinterred with Jacob are: Magdaline, Barrent, Maria, Jacob and Deborah Bloom, some of whom were identified in Jacob’s will as members of his family. Section 95, lot 1183.

BRADHURST, III, SAMUEL HAZARD (1749-1826). Captain. New Jersey Militia. According to the Son’s of the American Revolution’s Patriot Research Database, Samuel was born on July 5, 1749, in New Jersey to Anne Hannah Bradhurst and Samuel Bradhurst II.

Although little is known about his childhood, his adult life is well documented. The New York Journal of November 10th 1774, reported, “We hear from New Jersey that Mr. Samuel Bradhurst of this city, was admitted to the practice of Physic and Surgery by the Judge of the Supreme court . . . .”

The Patriot Research System also details that Samuel served as a medical officer and that he received his physician’s certificate in 1774. Referring to Samuel’s service during the Revolutionary War, the House Histree website records: “He trained as a surgeon and during the American Revolution served at the Battles of Princeton and Brandywine. While attending the wounded in 1777, he was captured by the British and placed under house arrest.” This is affirmed in a website article by the Borough of Ho-Ho-Kus, New Jersey entitled “The Hermitage: 250+ Years of American History” which states:

In fact, the English in 1777 placed a young, captured Rebel medical officer, Samuel Bradhurst, . . . under house arrest at The Hermitage. He would remain there through the war and would become a good friend of a visitor to the house, . . . Mary Smith. Samuel and Mary would marry at The Hermitage in December 1778.

According to the New Jersey Marriage Records 1670-1965, Samuel and Mary Smith applied for a marriage license on December 16, 1778. The United Stated Dutch Reformed Church Records in Selected States, 1639-1989 and the New Jersey Marriage Records, 1670-1965 chronicle that the couple were married on December 31, 1778 in Freehold and Middletown, Monmouth, New Jersey. As per the 1790 United States Federal Census, Samuel and Mary resided in the Mongomery Ward of New York City. There were ten household members, including two enslaved people.

Years later, Samuel started a wholesale drug business. Quoting Walter Barrett from The Old Merchants of New York City:

Soon after the war in 1786, I find him established at 64 Queen Street, corner of Peck Slip, in the commercial business as a druggist. In 1793, he took in a partner, doctor Samuel Watkins, and the firm was Bradhurst & Watkins. In 1795, they did a large business as druggists, at 314 Pearl Street, Doctor Bradhurst living next door at 315. The same year he founded the drug house of Bradhurst & Field, at 89 Water Street. In 1796 Bradhurst & Watkins dissolved. The partnership of Bradhurst & Field lasted many years . . . . A fire broke out in the drug store of Bradhurst & Field, at the corner of Pearl Street and Peck Slip, and before it could be got under, destroyed the store contents. The fire occasioned by the bursting of a bottle of ether. By this fire Bradhurst & Field lost $30,000, of which $2,700 was in bank notes.

The Revolutionary War and the fire at the drug store were not the only times Samuel’s life was upended. Walter Barrett continues, “The fire in Pearl Street was not the only one that visited Doctor Sam Bradhurst. On Tuesday evening, August 6, 1799, a house that he owned on the corner of Washington and Chambers Streets, was discovered to be on fire. The fire was extinguished before much damage had been done. It was unoccupied, and it was supposed that some enemy of the Doctor had set it on fire.”

In addition, as per House Histree:

In 1799, [Dr. Bradhurst] sold 20 acres in Harlem Heights to Alexander Hamilton (one of our Founding Fathers) on which he would build Hamilton Grange. Bradhurst was a friend of Alexander Hamilton and his wife, Mary, was a first cousin of Aaron Burr’s wife, Theodosia. In an attempt to keep the two from dueling, Bradhurst secretly challenged Burr to a duel with swords days before the fateful encounter with Hamilton. Burr escaped unharmed while Bradhurst was wounded in the arm.

Both Colonial Families of the USA and House Histree state that Samuel was a member of the Legislature. Colonial Families definitively records the year as 1802 while House Histree states that by 1804 he was “a Member of Legislature.” The New York Genealogical Records, 1675-1920 chronicles that Samuel’s place of residence in 1820 was New York City and he is listed as “physician.”

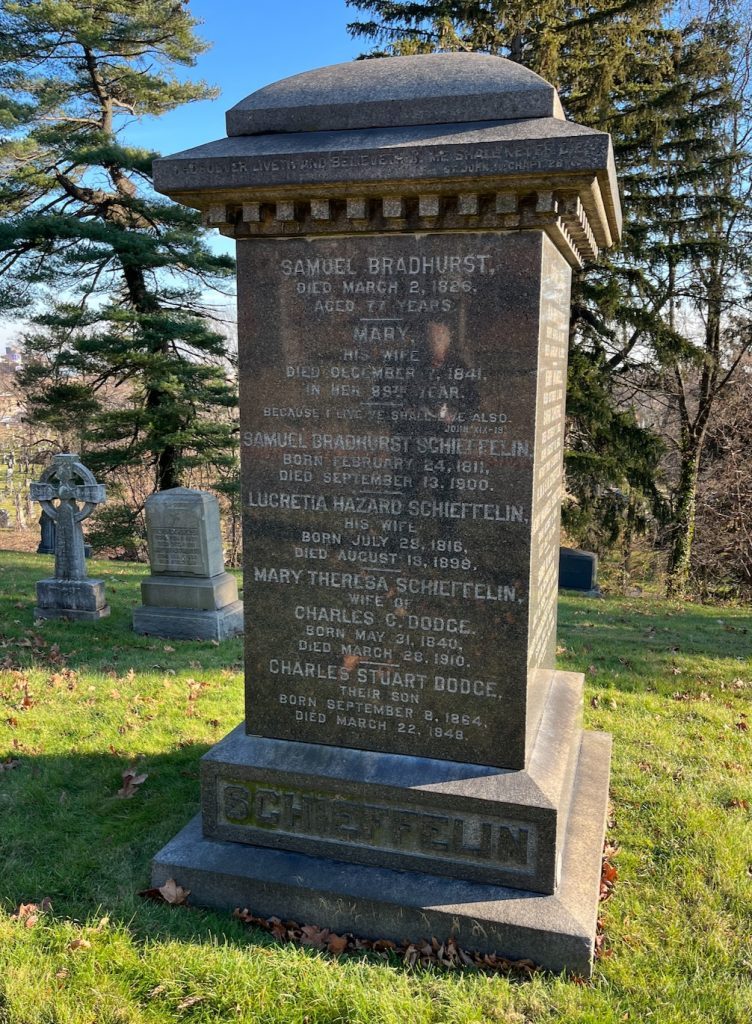

Samuel and Mary had five children: Samuel Hazard (1780-1883), John Maunsell (1782-1855), Elizabeth (1784-1802), Maria (1786-1872) and Catherine (1787-1868). Samuel passed away at the age of 79 on March 2, 1826, according to Green-Wood Cemetery’s chronological books. The New York Wills and Probate Records, 1659-1999 lists his probate date as March 14, 1826, and the probate place was New York City. Although buried initially interred in St. Luke’s Churchyard, Samuel’s remains, and those of his wife Mary (who died in 1841), were subsequently removed to Green-Wood Cemetery. As per the lists of New York Bodies in Transit, 1859-1894, his body was transferred to Green-Wood on April 16, 1879, and was interred on April 21, 1879. Section 119, lot 9472.

BRINKERHOFF (or BRINCKERHOFF), ABRAHAM (1745-1823). Member, Committee of 100; colonel, second regiment, Dutchess County. Several men had the name of Abraham Brinkerhoff during the Revolutionary War period; however, the research cited in this biography makes it likely that this man is interred at Green-Wood and was a patriot. Many of the historic documents use the alternate spelling of Brinckerhoff.

Abraham was born in New York City. According to United States Dutch Reformed Church Records in Selected States, 1639-1989, Abraham Brinkeroff was baptized in New York City on July 24, 1745. His parents were named as Joris Brinkerhoff and Maria Van Deusen (or Van Deursen). Joris Dircksen Brinckerhoff, Abraham’s great-great-grandfather, had settled in Brooklyn in 1638.

As per a family history, The Family of Joris Dircksen Brinckeroff, 1638, written by Richard Brinkerhoff (published in 1877), Joris, known as George, was a prosperous merchant, who grew up on a farm in Flatbush. Maria van Deusen was his second wife whom he married on October 23, 1742, two years after the death of his first wife, Elizabeth, with whom he had five children, three of whom died in infancy. Maria and George had six children, two of whom died in infancy. Richard Brinkerhoff notes that George built his store from bricks imported from Holland and that he and his son Abraham, who worked in his father’s store, had beautiful penmanship.

According to New York marriage records, Abraham married Dorothy (Dorothea) Remsen on December 17, 1772. The aforementioned family history reports that the couple had at least nine children: George (who died at age four), Peter, George, Maria, Abraham Jr., Lucretia, James Lefferts, and Jane. His marriage and children are also listed in the Genealogical and Family History of Southern New York and the Hudson River Valley, Volume III.

An Abraham Brinkerhoff, likely the man who is the subject of this biography, is listed as being a member of the Committee of One Hundred, organized on May 1, 1775, after the Battle of Lexington, to succeed the Committee of the City and the Committee of Sixty. The purpose of this group of established merchants was to “take possession” of New York City and support American independence. The Abraham Brinkerhoff of this biography was indeed a well-established merchant in New York City in 1775. The group was also known as the Committee of Resistance and the Provisional War Committee. Its first action was to seize vessels and many stands of arms for the impending war. The Committee of 100 also took action to disarm those who had commercial interests and supported the crown.

The answer to whether the Abraham Brinkerhoff who served in the military during the Revolutionary War is this same man is complicated because there are more than one man with that name in the New York area. According to New York Military in the Revolution, there is an Abraham Brinkerhoff who served with the rank of lieutenant colonel in the Second Regiment in Dutchess County, New York. It is uncertain if this man is the subject of this biography. That man served 22 days from October 6 through October 28, 1777, at Fishkill, New York, and was allotted 110 rations. That same man also served in a regiment that bore his name from April 7 through April 21, 1779. He is also listed as the colonel of Brinckerhoff’s Regiment of Militia, 1779-1880. His name appears on receipt rolls of subscribers who served under him 1779 and 1780, dated September 20, 1786.

According to Founders Archives.gov, there is a letter from George Washington to Major General Horatio Gates, dated October 1, 1778, followed by comments that mention Abraham Brinckerhoff, the colonel of the 2nd Dutchess County Regiment, who lived in Fishkill, New York. That letter suggests that the enemy was engaged in a foraging expedition in the area. George Washington was headquartered at a house in Fishkill, belonging to either Derick Brinkerhoff, who had been colonel of the 2nd Dutchess from 1775-1778 or Abraham. An expense account dated November 21, 1778, shows a payment of $20 at “Brinkerhoffs.” This information was verified by George Washington’s secretary, Robert Hanson Harrison. A Sons of the American Revolution membership application for a descendant of Derick and an Abraham Brinkerhoff, a private in the 2nd Dutchess County Regiment, whose life years were 1746-1795, make it impossible for that man to be the same Abraham Brinckerhoff, possibly the colonel, who is buried in Green-Wood.

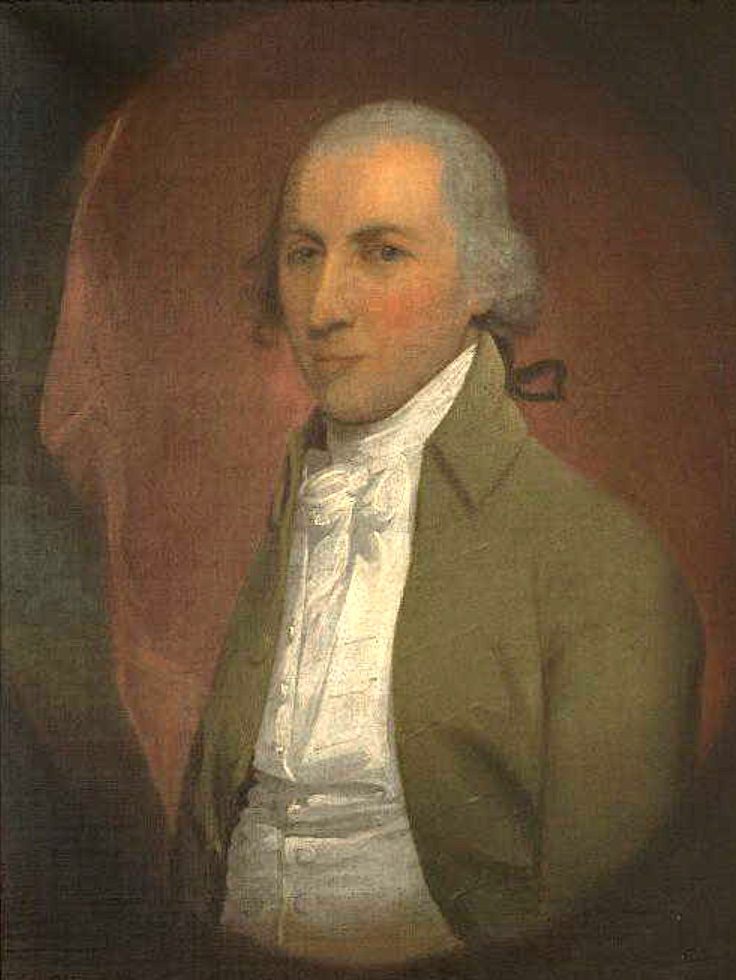

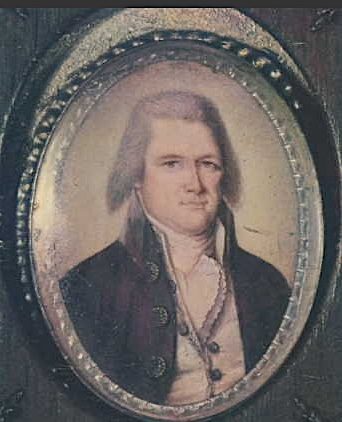

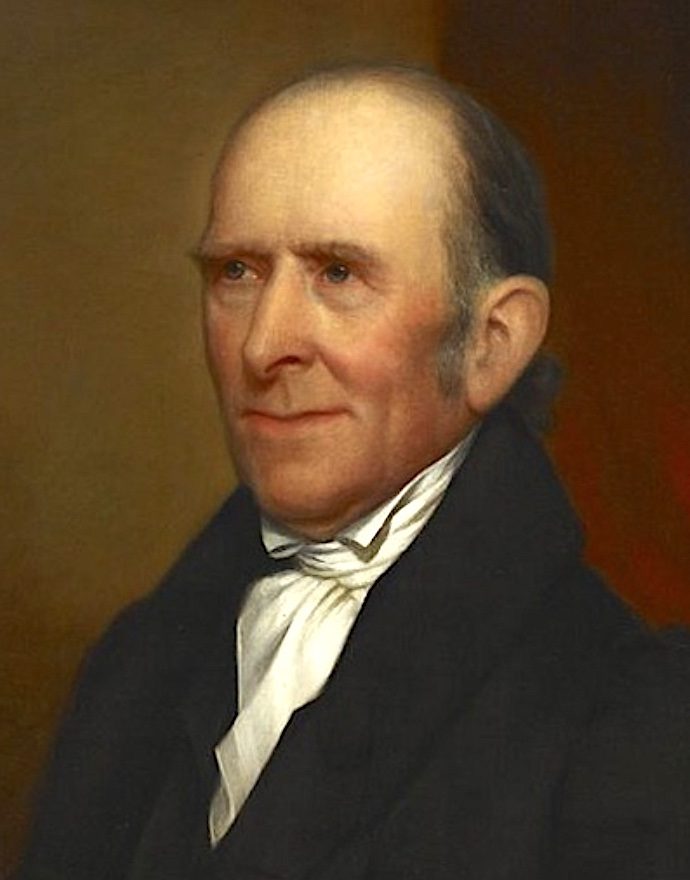

Abraham Brinckerhoff is listed in among the “Wealthy Citizens’ Biography in A Century of Banking in New York, 1822-1922. That entry notes that Abraham was taxed on $50,000 personal property in 1815 and $60,000 in 1820. The tax list of 1822 reports that he lived at 34 Broadway with his house valued at $11,000 and personal property at $60,000. His great wealth is mentioned in Early American Silver at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, a book written by Beth Carver Wees with Medill Higgins Harvey (2013) noting that the museum houses an ornately carved silver coffee/tea set that belonged to Abraham and Dorothea. Dorothea obtained the sugar and creamer at about the time of her marriage and the pieces, made by a New York silversmith, Myer Myers, are engraved with the initials of her maiden name, a common practice at that time. The description of the silver set, which the Met bought in 2012, notes that both Dorothea’s father and Abraham were dry goods merchants. Abraham’s portrait was painted by Gilbert Stuart in 1793-94 and Dorothea’s portrait was painted by John Trumbull in 1804-08. As per the New York Jury Censuses of 1816, 1819, and 1821, Abraham was listed as a “gentleman” living at 34 Broadway in New York City.

The New York Evening Post announced the death of Abraham Brinckerhoff at age 78 on March 7, 1823. New York Wills and Probate Records, 1650-1999, report that Abraham bequeathed his house at 34 Broadway with its furnishings and their summer house in Greenwich, Connecticut, to his wife as well as an annual payment of $5,000. His surviving children, grandchildren and members of extended family (John Schermerhorn, the husband of Lucretia) were listed in the will. Further, in a codicil to his will, Abraham revoked the appointment of his son George as one of the executors because George had not repaid him his debts. The will was dated January 23, 1822. On October 27, 1828, Abraham Brinckerhoff Jr. placed an ad in the Evening Post announcing that his father’s former summer residence in Greenwich, was available for lease. The home, in “perfect repair,” consisted of a large double house, stable and garden that was fully cultivated.

As per Green-Wood Burial and Vital Records, Abraham Brinkerhoff was previously interred elsewhere and was re-interred at Green-Wood on January 26, 1860, with his wife Dorothea, née Remsen, who died at age 85 in 1834, and other family members. Section 67, lot 10816.

BURBANK, ELIJAH (1762-1847). Private, Rhode Island and Massachusetts Regiments, Continental Army. Elijah Burbank’s ancestors settled in Massachusetts Bay Colony in the 17th century. His parents were Captain Abijah Burbank of Bradford, Massachusetts (1736-1813) and Mary Spring Burbank (1741-1786). Abijah Burbank, a miller, established the first paper mill in central Massachusetts in 1776, according to the Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation’s Millbury Reconnaissance Report, July 2007. Northern Illinois University’s Digital Library shows that Abijah Burbank petitioned to erect a powder mill on his land in Sutton, Massachusetts in 1776 to supply gunpowder to support the “great and important cause of America.” He was captain in several regiments in Massachusetts and Rhode Island during the American Revolution, per the History of Millbury.

Elijah Burbank was born in Sutton, Massachusetts on December 18, 1762 or 1763. He had several siblings, including Major General Caleb Burbank, Henry Burbank, Abijah Burbank, Mary Burbank Emery, Silas Burbank, and Nahum Burbank, per Find A Grave.com.

As revealed in his May 27, 1847 Brooklyn Eagle obituary, Elijah Burbank served under the age of sixteen in the Revolution in the company commanded by his father in Rhode Island. Elijah, in an effort to obtain a pension for his military service, swore in an affidavit dated June 7, 1837, and the Probate Court of Windsor County, Vermont, where he was then living, that he an enlisted in his father’s company in 1778, serving as a “master” to his father. The company then marched to Providence, Rhode Island, where it stayed about three weeks, then on to Greenwich and Newtown in Connecticut, then on to South Kingston, Rhode Island. Having served just over two months, he was discharged. In June 1780, he enlisted again and marched with his company to Hudson, New York, where he stayed for six weeks. It was then on to West Point, where he served with his regiment until October 31, when he was discharged. His widow, Mehitable Burbank, signed a court document on January 16, 1856, in Oxford, Maine, attesting that he was a private during the Revolution in the company commanded by Captain Benjamin Allton and, also, in Colonel John Rand’s regiment, enlisting in Worcester, Massachusetts on July 6, 1780. He was honorably discharged on October 10, 1780, per the company’s muster rolls and Commonwealth of Massachusetts records, as sworn by Burbank’s widow. His widow was granted a pension in 1858.

Massachusetts marriage records, 1633-1850, show that Burbank married Elizabeth Gibbs or Gibbes, known as “Betty,” on November 21, 1782. His wife was born in 1765 and the couple had two sons: Leonard Burbank (1783-1836), and Gardner Burbank (1785-1848), and likely four daughters: Polly (1787-1805), Eliza (born in 1788), Amelia (1800-1873), and Nancy/Anna.

Several of Elijah Burbank’s brothers became papermakers. According to his obituary in the Worcester Spy, Elijah Burbank owned the paper mills at Quinsigamond Village (now Worcester), Massachusetts, and furnished most of the paper for printing the Worcester Spy newspaper, as well as for the other publishers in Worcester. Papermaking by Hand in America by Dard Hunter, 1950, notes that Elijah’s mill introduced a paper machine that was operated by the family until 1836. A pictorial ream wrapper/label has been found with the name Elijah Burbank, Worcester, depicting an exterior view of the large Burbank mill. The mill had two vats, which would have been capable of producing from five to ten reams of paper a day. Isaiah Thomas, an early American newspaper publisher, depended upon this mill for much of the paper used in his Worcester printing business.

The 1790 United States federal census lists Elijah Burbank as head of household, living in Sutton, Massachusetts. There were two free white males under age 16 (presumably his two sons) and two free white females, for a total of six household members. By the 1800 United States federal census, Burbank was living in Worcester, Massachusetts and there were 20 household members, including eight free white males between the ages of 16 and 25. By 1820, the census shows the family still living in Worcester, with a total of 27 free, white people in the household. One person was engaged in manufacturing and one in agriculture. With the 1830 census, Burbank was still in Worcester and there were 16 free, white people living in the household. Betty Burbank died on September 22, 1831, in Massachusetts, according to her gravestone in Hope Cemetery in Worcester.

Burbank and Mehitable Marble were married on October 15, 1833, in Paris, Maine, based on a January 16, 1856 Oxford, Maine court document filed by Mehitable. In 1835, Burbank moved to Sharon, Vermont, according to an 1837 Probate Court document filed in Windsor County, Vermont.

Burbank was a papermaker for more than 60 years and sold his mills near Worcester to his sons. Green-Wood records show that Burbank died on May 26, 1847 of “remittent fever” at his son Gardner Burbank’s residence at 113 Willow Street in Brooklyn, and was interred at Green-Wood. He was described in obituaries as “a respected resident.” Gardner, who died in 1848, just one year after his father, is also interred in Green-Wood. Section 59, lot 1289, grave 79.

COLLINS, JR., HEZEKIAH (1739-1828). Lieutenant, Fifth Regiment, Dutchess County Militia. He was born in Westerly, Rhode Island, one of at least 11 children of Hezekiah Collins and Catherine Hosena Collins, according to the online database of the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR). In 1765, Hezekiah married Rhoda Ricketson in Dartmouth, Bristol, Massachusetts. The next year, the couple moved from Rhode Island to Beekman, in Dutchess County, New York. They had 13 children, all born in Dutchess, as per Descendants of John Collins of Charlestown, Rhode Island, and Susannah Daggett, His Wife, by Capt. George Knapp Collins (1901).

During the Revolutionary War, from 1775 to 1783 Hezekiah served in the Fifth Regiment of the Dutchess County (New York) Militia, according to documents related to the colonial history of the state of New York. Both the DAR and the SAR (Sons of the American Revolution) online databases confirm his service.

According to the 1790 census, Hezekiah was living in Beekman, Dutchess County, New York. His household, at that time, consisted of 15 people, all of them free white persons. The 1810 census reported that he was still in Beekman, but his household was now 9 free whites. As per the 1820 census, one enslaved person lived in his household, as well as 10 free whites.

Hezekiah was the 4th great-grandfather of Gerald Ford, the 38th President of the United States. He died in Union Vale, Dutchess County, New York, in 1828, at the age of 88. On December 22, 1850, his remains, and those of his wife Rhoda, were removed from their earlier place of interment to Green-Wood. At that time, Green-Wood recorded in its chronological books that Hezekiah Collins had been born in Rhode Island, was 88 years old at the time of his death, and had died in 1828. Section 90, lot 4807.

COPP, JOSEPH (1760-1837). Drum major, 3rd Connecticut Regiment. According to the Connecticut Town Birth Records, Pre-1870, Joseph was born on June 25, 1760, in New London, Connecticut, to Rachel and Joseph Copp. As per the Connecticut Church Records Abstracts, he was baptized on July 6, 1760.

Little is known of Joseph’s early life. Denison Genealogy: Ancestors and Descendants of Captain George Denison, by Everton Glenn Denison, documents that Joseph enlisted as a Continental soldier in the Connecticut Line on February 5, 1777 and served for the duration of the Revolutionary War. He served in Colonel Samuel Wyllys 3rd Connecticut Regiment in companies commanded by Captains Robert Warner and Henry Champion. Joseph began his military service as a drummer and was promoted to drum major on September 1, 1780. He was discharged on June 13, 1793. Jospeh’s military history is substantiated by two sources: the Connecticut Revolutionary War Military Lists and the Record of Connecticut Men in the Military and Naval Service. The website Rev War Talk records that Colonel Wyllys commanded the 3rd Connecticut Regiment 1777-1781. The regiment served in the New York area through much of the war; in all probability, Joseph was in New York for much of his service.

As per the Denison Genealogy, Joseph married Hannah Crary on an unspecified date; the couple had five children: Betsey, Hannah, Nancy, Joseph and Maria Adeline. Their marriage and number of children are corroborated in Genealogy of the Descendants of William Chesebrough of Boston, Rehoboth, Massachusetts, by Anna Chesebrough Wildey.

As per the 1800 and 1810 federal censuses, Joseph and his family resided in the Stonington-New London section of Connecticut. The 1820 and 1830 federal censuses document that the Copp family lived in New York City.

Death notices in the New York Daily Herald and The New York Evening Post report that Joseph passed away on September 9, 1837, at the age of 78, in Middleton, Connecticut. The Evening Post’s notice states “Mr. Copp was one of the few survivors of the Revolution, and an old and respectable inhabitant of the city.” Joseph, Hannah, and their son, Joseph Jr. were originally buried in Connecticut. According to Green-Wood’s Chronological Book entries, they were reinterred at Green-Wood on December 3, 1846. As per the transcription, under Notes and Remarks, their remains were removed from the Presbyterian Burial Ground on Houston Street in Manhattan. Their daughter, Betsey, passed away in 1859 and is buried with them. The Copp-Waring Family Monument at Green-Wood is, in part, illegible, especially the dates of death for Joseph, Hannah, and their son. On the other side of the monument are the names of another daughter, Maria Adaline, her husband, Samuel Waring, and their descendants. Section 90, lot 1448.

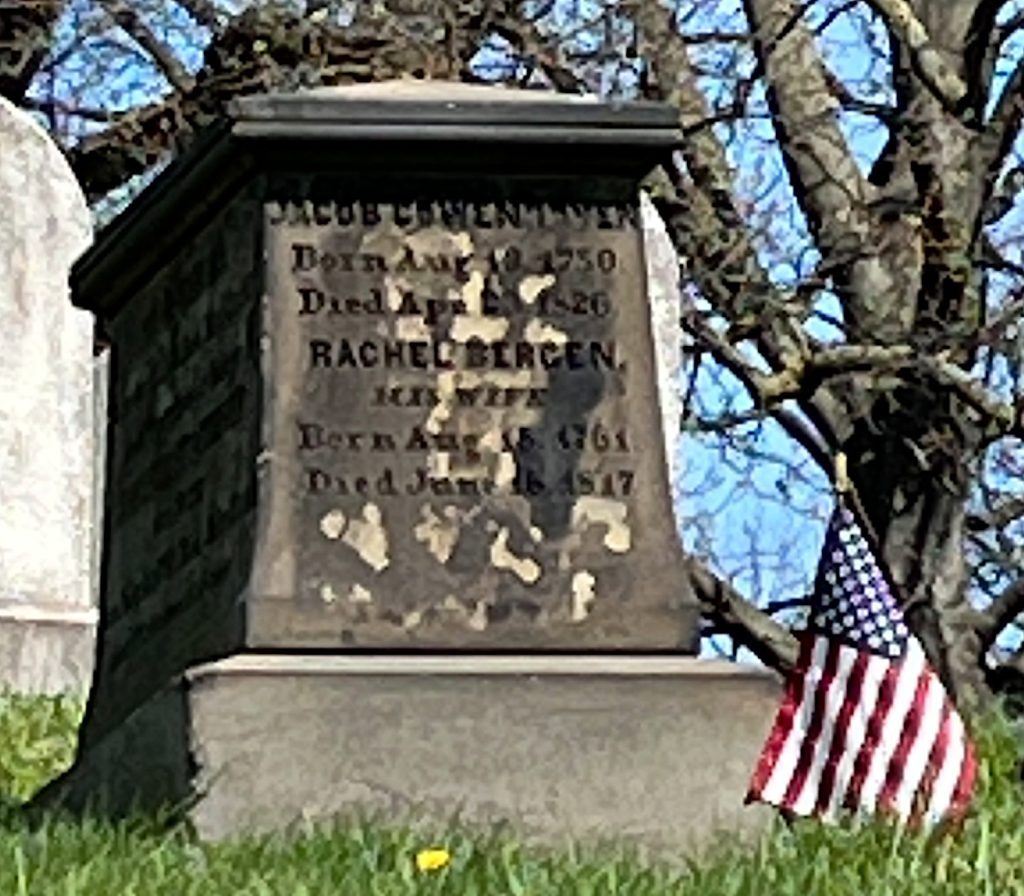

COWENHOVEN, JACOB PETER (1750-1826). Captain, Light Horse Militia of Monmouth County, New Jersey. Born Jacobus Couwenhove on August 13, 1750, in Red Hook, Brooklyn, Jacob’s parents were Pieter Jacobse Couwenhove (1718-1753) and Cathrina (or Catharine) Roelofse Schenk (born 1718), according to family genealogical sources. Baptismal and confirmation records are contradictory. As listed in the New Jersey Births and Christenings Index, 1660-1926, Jacob was christened on August 26, 1750, at the Dutch Reformed Church, Freehold and Middletown, Monmouth County, New Jersey. The United States Dutch Reformed Church Records from Selected States, 1660-1926, show that he was baptized on September 22, 1750, in Freehold and Middletown, New Jersey. The Cowenhoven family descended from Wolphert Gerritson Van Kouwenhoven, who immigrated from the Netherlands to the town of New Utrecht in the Dutch colony of New Netherland (later New York) in the 17th century, as recorded in the Conover and Cowenhoven family papers held in the Center for Brooklyn History.

New Jersey Tax Lists Index 1772-1822 show Captain Jacob Covenhoven living in Middletown Township, Monmouth County, New Jersey, in 1779. An American Revolutionary War patriot, Jacob was captain of the Light Horse Militia under the command of Colonel Asher Holmes. According to North America, Family Histories, 1500-2000, prior to the British army’s occupation of New York City, Jacob was sent to Sandy Hook, New Jersey, where he smashed the lamps of the lighthouse in the hopes of making the British fleet’s arrival more difficult. Revolutionary War rolls show that he participated in the Battle of Monmouth as a captain in the 1st Regiment. Jacob was taken prisoner near Middletown Point and almost hanged as a rebel. In fact, he was a prisoner of war twice. The first time he was exchanged, but the second time he was confined in the Livingston Sugar House Prison and nearly starved to death.

Eventually paroled, in 1778, to the farm of Elisha Berger on Long Island, per Revolutionary War Military Service Records, Jacob met his future bride Rachel Bergen there and they married on May 10, 1780. Rachel’s date of birth on her gravestone at Green-Wood shows August 15, 1761. Their New York marriage license was dated April 21, 1780, with Jacob’s surname as “Conover,” a name used instead of Cowenhoven in several documents. Rachel was a daughter of Tunis Bergen and Johanna Stoothoff, of Brooklyn. Children quickly followed and included Sarah Ann Conover Dey (1780-1867), Peter Jacobus Conover (1783-1842), Johanna Conover (1785-1864), Catherine or Catharine Conover Jackson (1787-1833), and Phebe Conover (1789-1833.)

Jacob’s name appears on Revolutionary War Military Service Records and payroll records through at least 1782. After the war, per North America, Family Histories, 1500-2000, the family resided on Jacob’s farm in New Jersey until after 1796 and then on a small farm of about 16 acres, purchased on August 13, 1804, from his father-in-law, Tunis Bergen, located in Brooklyn, in the vicinity of Hamilton Avenue and Court Street and overlooking Governor’s Island. The property had been bought by Tunis Bergen, on August 22, 1801, from the executors of the estate of Jeremiah Vanderbilt, of Hempstead, Long Island.

An 1801 document in the Conover and Cowenhoven family papers collection at the Center for Brooklyn History is concerned with an agreement between Jacob Cowenhoven and York Lyell regarding a debt between them and an arrangement to pay this debt via the work and labor of a presumably enslaved Black man, Robin John Johnston. Another such document, dated December 1826, concerns the transfer of a “servant girl,” Mary Ann, described as the daughter of a woman named Elizabeth, who had been enslaved by “Jacob Conover.” The final emancipation of enslaved people in New York State did not occur until 1827.

As carved on the gravestone in Green-Wood erected for Rachel and Jacob, Rachel died on June 16, 1817. Jacob signed his will on October 3, 1823. At that time, he was living in Brooklyn.

Jacob lived until April 23, 1826. An ad, placed in the Long-Island Star of April 3, 1828, lists the farm and 16 acres of real estate of Jacob Cowenhoven, deceased, for sale or rent. The land was situated near Red Hook in what was then the town of Brooklyn, Kings County, and a horse ride of 15-20 minutes from the Brooklyn ferry. A house, separate kitchen, barn, and “other necessary buildings” were part of the offering. The ad stresses the extensive and beautiful view of the bay and harbor of New York City from the property and the impending “opening of the streets” that will bring the land into the “immediate vicinity of the village of Brooklyn.” The executors of Jacob’s will were his son, Peter Conover, and nephew, Garret Bergen.

Per Green-Wood records, the bodies of Jacob and Rachel were removed from the Bergen family burial ground in Gowanus, Brooklyn, and reinterred in Green-Wood on December 11, 1849, near Rachel’s parents and other members of the Bergen family. Their daughter, Johanna, and possibly their son, Peter Conover, are also interred in Green-Wood. Section 43, lot 267.

DAVIS, DAVID (1754-1858). Continental Army. One of more than a hundred men with the same name listed in the Revolutionary War muster rolls, our David Davis was born on January 15, 1754, in New Jersey, according to information recorded at the time of his death. According to the same document, David Davis was a widower, and lived for 104 years, 10 months, and 27 days. His last residence was on Cumberland Street, in the Fort Greene neighborhood of Brooklyn.

Beyond those dates and details, hardly any information was recorded or preserved about this veteran of the Revolutionary War.

The same David Davis is thought to have enlisted in the New York Regiment on June 28, 1775, according to the United States Military Rolls. He would have been 21 years old at the time. He is also thought to be listed in the 1782 muster rolls of New York’s 2nd Regiment as a fifer. In the Continental Army, as in European armies, fifers (and drummers) kept marching pace and relayed orders to soldiers in the field, in the form of musical signals.

Possibly the same David Davis is located in the federal census of 1790 in Mount Pleasant, Westchester County, part of a household of three “free white persons-male” age 16 and over, three “free white persons—female,” and one male under age 16.

He is likely the same David Davis as is listed as a Revolutionary War Pensioner in records from 1818 to 1848. He might be the same David Davis located in the New York census of 1840 in Brooklyn’s 5th Ward, at 82 years old, although in fact he would have been 86 years old.

At the time of his death in 1858, the New York Evening Post noted: “He served during the whole of the war of independence and was for many years attached to the Brooklyn Navy Yard. The old veteran died in the full possession of his mental faculties.” Section 190, lot 18208.

DELAFIELD, JOHN (1748-1824). Merchant. Born in England, he was one of the first men from that country to come to live in America as the Revolutionary War drew to a close. When he arrived in New York City in the spring of 1783 it was still occupied by British troops, and he brought with him the first copy of the provisional treaty between the United States and Great Britain to reach America. He arrived in this new land with considerable wealth, was by descent a “Count of the Holy Roman Empire,” and by the turn of the century was one of the wealthiest men in New York and was called “one of the fathers of Wall Street.” His mansion across the East River from New York City, which he occupied with his wife Ann Hallett (who was herself a member of a prominent Revolutionary family) and their eleven children, was one of the great houses of its period. He was an original director of the Mutual Insurance Company of New York when it was organized by Alexander Hamilton in 1787 and was later president of the United Insurance Company.

Delafield suffered great financial losses during the War of 1812 from the marine insurance which he underwrote. His sons John, Richard and Edward were able to restore the prosperity of this family and to carry on its tradition of leadership. Section 36, lot 3977.

DUYCKINCK, GERARDUS (1723-1797). Member of the Patriot Committees of 51 and 100, delegate to the Provincial Congress. A “Gerardus Duyckinck” is listed as a member of New York City’s Committees of 51 and 100, a group of patriot leaders organized in New York City in 1775. Those committees are described in the supplement to New York in the Revolution: As Colony and State:

Though Gerardus Duyckinck is an unusual name, there are three consecutive generations of men of the same family named Gerardus Duyckinck who lived in the New York City area in the 18th century. Gerardus Duyckinck (1695–1742), who married Johanna Van Brugh, was the father of Gerardus Duyckinck (who was born in 1723). Gerardus Duyckinck (1723–1797) married Ann Rapalje, and they were the parents of Gerardus Duyckinck (1754-1814), who married Susan Livingston.

While Green-Wood’s burial records list a Gerardus Duyckinck as removed to the cemetery in 1860, and apparently removed with his wife, the cemetery clerk who recorded that removal made our efforts to identify which Gerardus is at Green-Wood more difficult by listing a “Mrs. Duyckinck” with no first name.

Clearly, the first Gerardus noted above, who died in 1742, could not have been the Revolutionary War patriot. Nor is it likely that he was the Gerardus removed to Green-Wood in 1860—such gaps between death and removal of over a century would be highly unusual. Further, the third Gerardus, born in 1754, is very unlikely to have been the patriot—based on our research into eight other members of the Committee of 100, they tended to be well-established in the mercantile community, and to have typically been in their 40s or 50s when they joined that group in 1775. In researching members of the Committee of 100, we have identified men interred at Green-Wood with the following years of birth: 1713, 1724, 1726, 1728, 1736, 1739, 1742, and 1745. 1723 is well within this range; 1754 is not.

The Gerardus who was born in 1754 was only 21 years old in 1775—likely too young to have established himself in the merchant community, as was typical for those who served on these committees. Indeed, the Brooklyn Standard Union of July 1, 1929, reports that “the most progressive advertiser in the formative days of American advertising [was] Gerardus Duyckinck, who conducted a general store in New York and began advertising in the 1750s.” Given their life dates (the first Gerardus already dead; the third just born), neither of the other two men of this name could have been advertising in the 1750s and establishing two decades of success as a merchant. This Gerardus, as reported on the WorthPoint website (a place for assessing the monetary value of art), who was then still in his early twenties, became a merchant by taking over his father’s business of “Limning, Painting, Varnishing, Japanning, Gilding, Glazing, and Silvering Looking-Glasses” near the Old Slip Market in Manhattan. His business later morphed into sales of spectacles, telescopes, maps, prints, and art supplies. He also appears to have been a painter. In his will, probated soon after his 1797 death, he left his son Gerardus “Painters Colours, Drafts, Prints, and Implements for painting for his own use. . . .” Further, as per Find A Grave, the third Gerardus, who was born in 1754 and died in 1814, is interred in Poughkeepsie Rural Cemetery; the photograph on that website of his gravestone shows those life dates. Therefore, by process of elimination, the second Gerardus above, with life dates 1723-1797, is likely the person of that name interred at Green-Wood—and the patriot.

It is also significant that the Duyckincks were removed to Green-Wood’s lot 10776 (purchased by the Dutch Reformed Church) in 1860 with John Holthuysen and “Mrs. Holthuysen.” Records establish that the Duyckincks and Holthuysens intermarried; Johanna, the niece of the Gerardus who was born in 1723, married John Holthuysen’s son. Thus, that Gerardus and John were contemporaries and in-laws—and it would be expected that they would be removed together. Further, as per U.S. Newspaper Extractions, this Gerardus’s wife, Ann (whom he married in 1752), died in 1811 at the age of 78, as reported in the New York Evening Post; she therefore might well be the “Mrs. Duyckinck” who was removed in 1860 to Green-Wood with her husband Gerardus.

Gerardus Duyckinck was born and baptized in 1723. His parents were Gerardus and Johanna Duyckinck. Gerardus married Ann Rapalje in 1752; they had three children: Gerardus, Johanna, and Diana.

Gerardus Duyckinck’s name appears on a July 1776 list of New York City citizens from whom “window leads” were seized from their houses by patriot authorities. Patriot forces needed lead for bullets to fight the war, but no accessible lead mine existed and lead could not be imported. Therefore, the commissary of the Provincial Congress sent men out to gather the lead that held residential window panes in place; over 100 tons were gathered, and receipts were given for this lead; payments were made after the war. In one documented example, 124 pounds of lead was taken from the house of Dr. Paulus Banta in July 1776; he was paid for it in December 1784.

A document in the collections of the New-York Historical Society Museum and Library and dating from the Revolutionary War also lists “Gerardus Duyckinck” as one of 100 individuals who would be serving in the Provincial Congress for the City and County of New York “in the present alarming Exigency.” This, again, is likely the man of that name who was interred at Green-Wood in 1860. The records of the Dutch Reformed Church, of which he was a member, record his death and burial in 1797. His will, probated that same year, named his son Gerardus and Abraham Brinckerhoff (see) as his executors. His remains now lie in the Dutch Reformed Church’s lot at Green-Wood—the same lot in which Brinckerhoff is interred. Section 28, lot 10776.

ELLET, ELIZABETH FRIES LUMMIS (1812-1877). Writer and historian. Born in Sodus Point, New York, on the shore of Lake Ontario, she showed an interest in writing poetry as a child. Her first writing was published in 1834. The next year she married William Henry Ellet, but continued to write books, poems, translations, and essays on European literature. In 1845-1846, while on an extended visit to New York City, she competed with Frances S. Osgood in writing flirtatious poems to Edgar Allen Poe, who published them in his Broadway Journal. Their rivalry turned bitter when Elizabeth began circulating rumors that Poe and Mrs. Osgood had been intimate. When Mr. Osgood threatened a libel suit, she toned down her claims. However, this gossip followed Mrs. Osgood until her death. In 1848 Elizabeth Ellet returned to New York City. She soon turned her wrath on Rufus Wilmot Griswold, whose anthology The Female Poets of America (1848) had treated her work with less than enthusiasm. She was able to convince Griswold’s ex-wife to sue to have their divorce decree vacated; this resulted in the breakup of Griswold’s marriage.

Though Elizabeth Ellet continued to write many articles for periodicals, she now turned to writing history books. Realizing that there was virtually no published material on the role of women during the Revolutionary War, she conducted her own research, studying unpublished letters and interviewing descendants. Her The Women of the American Revolution was published in two volumes in 1848; a third volume was added in 1850. She also wrote Domestic History of the American Revolution (1850), Pioneer Women of the West (1852), Women Artists in All Ages and Countries (1859), and The Queens of American Society (1867). These books made her the first American writer who emphasized the role of women in American history. Section 41, lot 3599.

FELLOWS, JOHN (1759-1844). Colonel, Minuteman, Massachusetts Militia. As per Biographical Sketches of the Graduates of Yale College with Annals of the College History, July 1778–June 1792, John was born on November 17, 1759, in Sheffield, Massachusetts, to Ezra and Charity Fellows. According to Geni.com, Ezra was a major in the Continental army. The Massachusetts, U.S., Town and Vital Records document that John had three sisters, Charity, Pamela, and Huldah.

Little is known of John’s early life. Biographical Sketches of the Graduates of Yale documents that, in 1775, at the age of sixteen, he enlisted to serve for three months as a Minuteman under the command of his uncle, General John Fellows. His profile on Geni.com states, “During the Revolutionary War, John Fellows fought in Captain Bacon’s company, Colonel John Fellow’s regiment, with the Massachusetts line at sixteen years of age. He participated in the Siege of Boston and Bunker Hill. He was called John Fellows Jr. to distinguish him from his uncle General John Fellows who fought with Washington at Long Island.”

After the war, John attended Yale University, and subsequently enrolled in Dartmouth College in June of his freshman year. He returned to Yale two years later and graduated in 1783. John is listed in the 1816, 1819 and 1821 Ward Jury censuses as a resident of New York City. According to the 1816 census, he resided on Courtland Street in Manhattan and worked in a military store. As per Biographical Sketches of the Graduates of Yale College, he began his career as a New York City bookseller and publisher in 1795.

His profile on Geni states that he applied for a Revolutionary War pension on June 27, 1838, at the age of 77. This is confirmed by his listing in the U.S. Revolutionary War Pensioners of New York City. According to his Yale profile, “Later in life he followed the business of an auctioneer, and was subsequently a constable in the city courts.” As per the entry on Geni, “He was still a teacher in New York City in 1838 at the age of 87.” According to Appletons’ Cyclopedia of American Biography, in 1843, John published The Veil Removed: Reflections on Humphrey’s Essay on the Life of Israel Putnam, an historical biography on the life of General Putnam, a renowned American patriot. He also published Exposition of the Mysteries or Religious Dogmas and Customs of the Ancient Egyptians, Pythagoreans, and Druids and The Mysteries of Free Masonry; or an Exposition of the Religious Dogmas of the Ancient Egyptians.

John passed away on January 3, 1844 in Manhattan. An obituary in the New York Tribune states:

Colonel John Fellows, a relic of “the time that tried men’s souls,” died yesterday in our city, aged 84. He was a companion and friend of Thomas Paine, and we believe also of Thomas Jefferson, of whom he was a warm admirer, and possessed a vast fund of information with regard to the men of the last and preceding generations . . . . He has lived to a good old age, and when we last saw him, but a few weeks since, he seemed as hale and vigorous as at any time these five years. Peace to his memory!

Death notices were also published in The New York Evening Post and the Litchfield Enquirer. He posthumously received a monetary award at a special meeting of assistant aldermen on February 5, 1844. As reported in the February 7, 1844 edition of The Evening Post, G. Vale was paid the amount due to John for his service as marshal of the Superior Court. According to Green-Wood’s chronological book entries, John died of peri-pneumonia and was interred on January 6, 1844 (three days after his death). The entry in Green-Wood’s chronological book erroneously records his place of birth as Connecticut. Section 17, lot 210.

GIBSON, HENRY (1751-1852). Soldier, First and Third New Hampshire Regiments; Commander-in-Chief’s Guard, Continental Army. Almost everything known about Henry’s life and military service comes from 19th-century newspaper articles about him, describing events he recalled almost 70 years after they occurred.

Henry was born in 1751, either in Orange County in New York, or on a ship at sea to Irish parents migrating to the colonies, landing in Boston and settling in New Hampshire. He grew up either in New York or New Hampshire; both origin stories are equally plausible.

At age 24, Henry enlisted as a soldier in Boston after the Battle of Bunker Hill, which had occurred on June 17, 1775. He was mustered into the regiment of Colonel Henry Dearborn, who fought with the First and Third New Hampshire Regiments. During his five-year enlistment, Henry was present at the Battles of White Plains (October 26, 1776); Brandywine, Pennsylvania (September 11, 1777), where he was wounded by a musket ball in the left shoulder; and Monmouth, New Jersey (June 28, 1778). From June to October 1779, Henry’s regiment participated in the Sullivan Expedition, a campaign against the four British-allied nations of the Iroquois. The campaign was particularly cruel: General Sullivan destroyed 40 Iroquois villages, in what some have called genocide.

Henry’s stint was up in the summer of 1780. He then enlisted in a horse battalion and was soon transferred to the Life Guard, officially known as the Commander-in-Chief’s Guard, also known as the First Guard. This was General Washington’s personal guard, formed in 1776 to protect him (the British had put a price on his head), as well as the money and official papers of the Continental Army. Although no description or image of Henry’s appearance exists, there is a description of the kind of men Washington wanted in the Guard:

His Excellency depends upon the Colonels for good Men, such as they can recommend for their sobriety, honesty, and good behaviour; he wishes them to be from five feet, eight Inches high, to five feet, ten Inches; handsomely and well made, and as there is nothing in his eyes more desirable, than Cleanliness in a Soldier, he desires that particular attention may be made, in the choice of such men, as are neat, and spruce.

Henry witnessed the surrender of Cornwallis at Yorktown, Virginia, in October 1781. The Guard was stationed in Newburgh, New York, from that time until the conclusion of peace negotiations with the British in May 1783. Upon discharge at Newburgh, Henry was among the Guards who volunteered to accompany General Washington and his possessions back to his home at Mount Vernon, Virginia. In 1815, almost all records of the Life Guard were lost in a fire at Charlestown Navy Yard.

As a civilian, Henry settled in Orange County, New York, where he might have grown up. In the federal census of 1800, 49-year-old Henry was probably married with three children, judging by the ages and sexes of the members of his household. By the time of the 1810 federal census, there seemed to be five children. Between 1800 and 1850, the decennial reports located Henry in various towns in Orange County. By 1850, Henry was 99 years old; his occupation was listed as “revolutionary soldier,” and his industry was “retired.” He may have been living with his daughter and possibly with two grandchildren. That year, an article appeared in the Williamsburg Daily Gazette, headlined “The Last of Washington’s Life Guard,” recounting the story of Henry’s military service and asking if there were any other survivors of “that distinguished band.”

In 1852, Henry reappeared in the news in articles on the celebration of George Washington’s 125th birthday, on the 24th and 25th of February. In the New York Tribune, 101-year-old Henry was profiled as living in very poor circumstances, subsisting on a small government pension of $96 per year, and as the sole support of his grandchildren. The article noted that he was to appear at Niblo’s Garden, a popular New York City place of entertainment, later that day. According to the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, a collection was taken up during one of the celebration dinners by several of the companies of soldiers. Henry received $60 and was named an honorary member of all the companies. They pledged that he would not want for anything for the rest of his life.

Henry died a few weeks later, on March 15. He was given a full military funeral with honors. His body rested in state for several days in New York City Hall, and his funeral procession wound from there down to the Fulton Ferry landing for the trip to Brooklyn and Green-Wood Cemetery. The procession was made up of more than 5,000 people, including military units from the National Guard, and the Continental companies of New York, Brooklyn, and New Jersey, as well as public officials, one of Henry’s granddaughters, and a long-lost son, who, having read about his father’s death in the news, raced to join in the procession. In the audience at City Hall was another “Interesting Relic” of the Revolutionary War (as a newspaper article had put it): Asa Holden (see), who had also attended Washington’s birthday celebration, and would be buried in Green-Wood Cemetery the following year. Section 85, lot 7276.

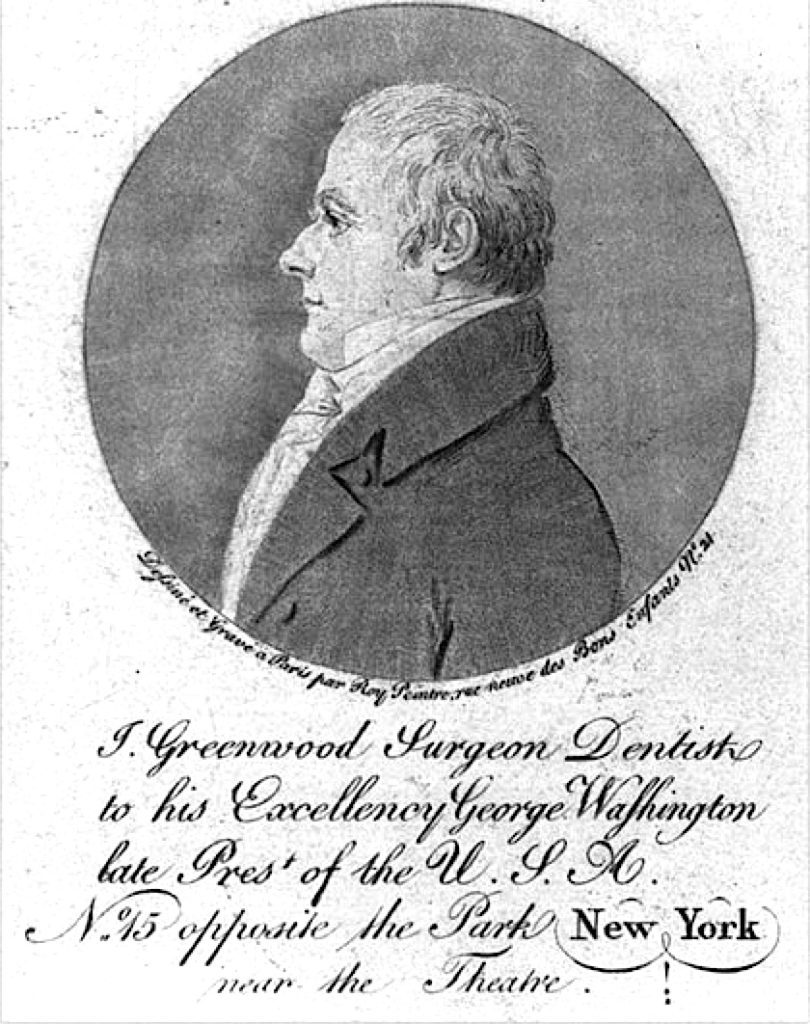

GREENWOOD, JOHN (1760-1819). Fifer, Continental Army. Born in Boston, Massachusetts, on May 17, 1760, to Isaac Greenwood and Mary Jans or I’ans, both also born in Massachusetts, he was the grandson of Isaac Greenwood, the first Hollisian Professor of Mathematics and Natural Philosophy at Harvard College, per the Harvard Mathematics Department Timeline. His son, also Isaac, and John Greenwood’s father, was the first native-born American dentist and a maker of mathematical instruments. According to North America, Family Histories, 1500-2000, Isaac was said to have constructed the first electrical machine for Benjamin Franklin. The couple had two other sons: Isaac, 1757-1829, and William Pitt, 1766-1851, according to Find A Grave website.

John Greenwood lived in Boston for most of his early life and had little formal education. According to Wikipedia, he had a “troubled” childhood and was apprenticed to a cabinetmaker at an early age. He became close friends with his father’s apprentice, Samuel Maverick, a seventeen-year-old who would die in the Boston Massacre of 1770. According to The Washington Library at Mount Vernon’s Digital Encyclopedia, John “saw the tea destroyed during the Boston Tea Party as well as several colonial officials tarred and feathered, all before he turned thirteen years old.” Greenwood learned to play on a fife some of the tunes that he heard the British regulars who were occupying Boston play. He was sent to live with his uncle Thales Greenwood, working as an apprentice cabinetmaker in Falmouth, now Portland, Maine.

In his autobiography, Greenwood wrote that, in May 1775, when he heard the news that the first shots of the American Revolutionary War had been fired in the Battles of Lexington and Concord, he walked, alone, the 150 miles to Boston, occasionally stopping in taverns to play music for soldiers. According to his memoirs, he enlisted, on May 3, 1775, in Captain Theodore Bliss’s company of the 26th Massachusetts Regiment of the Continental Army as a fifer, serving for about 20 months. He saw part of the Battle of Bunker Hill, scouted for Benedict Arnold’s expedition to Canada, and took part in the campaign around Trenton, New Jersey.

According to his memoirs, housed at The University of Michigan William L. Clements Library, he became a privateer after 1777, intercepting British ships in the West Indies. According to North America, Family Histories, 1500-2000, he sailed under Captain John Manly and others. He was four times a prisoner of war by the British, having been captured the last time while in command of a six-gun schooner, but escaped from prison each time. He was able to make some money by the time the war formally ended in 1783.

Greenwood settled in New York at the close of the war, studied dentistry, and, by 1785, had established a dental practice there. He is credited with originating the foot drill, spiral springs to hold plates of artificial teeth in place, and the use of porcelain for false teeth.