Sue Ramsey has done it again!

Sue is one of Green-Wood’s Civil War Project’s wonderful–and tremendously dedicated–volunteer researchers. Retired from the Southern California Gas Company, she has been working her way, since 2005, through the now 5,200 volunteer-researched and written online Civil War biographies (thanks Susan Rudin for your incredible work translating all of this research into biographies!) of veterans who are interred at Green-Wood. Sue does careful and time-consuming follow-up research to flesh out biographies and solve mysteries. It was Sue who made it possible and inspired me to wrote my third, and most recent, book: “The Gallant Sims”: A Civil War Hero Rediscovered.

For more on Captain Samuel Harris Sims, go here.

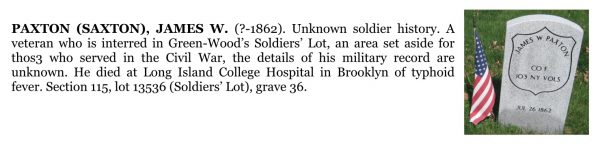

Sue recently came across the biography below, one of 5,200 we have on our website of Civil War veterans–as well as those who did not serve in the military but otherwise participated in the Civil War (as nurses, members of the Sanitary Commission, organizers of Sanitary Fairs, etc.):

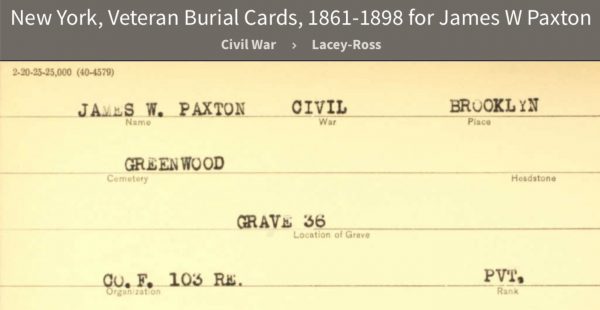

Sue routinely sends me her latest research masterpiece as an attachment. As she started her work on this one, she included this card:

I immediately recognized this card. About 15 years ago, I was headed off to Proctor, Vermont, for the Association of Gravestone Studies annual convention. On the way, I stopped at the New York State Military Museum in Saratoga Springs. I knew a volunteer up there and he had offered to show me around. It was a fascinating place–both for its public displays and its storage. As he showed me through one of its offices, I asked him what was in the file drawers. Not sure, he opened one up and, lo and behold, it was filled with cards just like the one above. It soon became apparent that this was an alphabetical catalogue of all of the U.S. Government-issued gravestones for veterans interred in New York State cemeteries. Because I was already trying to find as many of the Civil War veterans interred at Green-Wood as possible, I realized that these drawers were like manna from heaven for me! Fortunately, the convention I was on my way to was not scheduled to start for another day–so I spent the entire next day going though thousands of these cards, culling those with “GREENWOOD” on them.

This card was the trigger for the online Paxton biography we had posted soon thereafter. I was able to find James W. Paxton listed in Green-Wood’s archives–he is in section 115, lot 13536–the Civil War Soldiers’ Lot–grave 36 (the grave specified on the card above). According to Green-Wood’s chronological book, Paxton died on July 26, 1862, at Long Island College Hospital in Brooklyn, of typhoid fever. Unusually, Green-Wood did not record his marital status or his age at the time of death. This would seem to indicate that no one familiar with his roots was around to supply that information as he was about to be interred.

Note that, according to the biography we had online (the one reproduced above), Paxton’s soldier history was unknown. Though the index card above indicates he was a private in the 103rd Regiment, Company F, I was unable to find his name on the muster roll for what I assumed was the 103rd New York Infantry.

So, here’s where Sue’s remarkable research comes into play. In the Historical Date Systems Civil War database, the most complete Civil War database online, she found no matching soldier named James Paxton who had served in the 103rd New York or any other New York State regiment. Nor did she find a James Paxton in New York City’s death records. He was not listed in the Bodies in Transit database (one of Sue’s very favorites, listing bodies being shipped through New York City–a very valuable research tool for men who died in battle or at the front of disease–and for discovering spelling variations in their names). Nor could she find anything about a soldier named James Paxton, who had died in 1862, in several other databases.

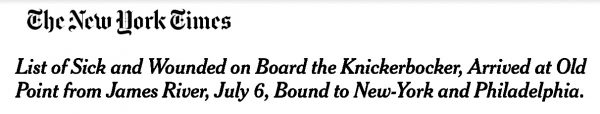

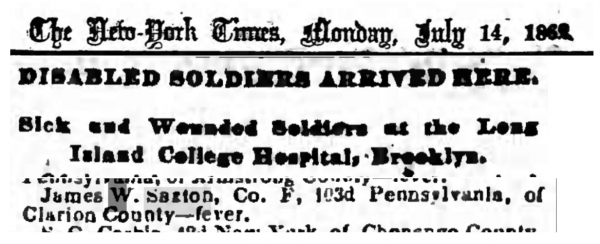

But when she searched New York newspapers online, she hit pay dirt with these entries:

Even better, the Times, in this article, listed some of the sick and wounded by name, including a “Ja[me]s W. Saxton” of the 103rd Pennsylvania Infantry, Company F. That notation–Pennsylvania–explained why neither Sue nor me could find Paxton on the muster roll for the 103rd New York Infantry. We had assumed he had served in a New York regiment–but that turned out not to be the case. Each state organized its own regiments and numbered them in sequence–and both New York and Pennsylvania were large enough that they got up to–and well beyond–103 infantry regiments.

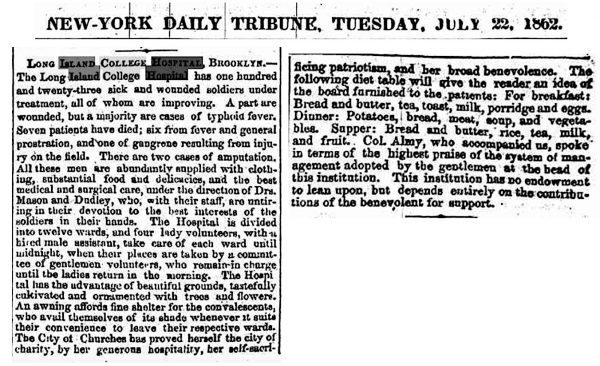

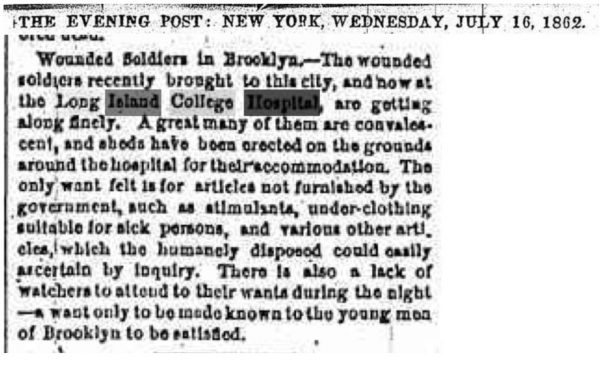

Here’s a more general report on the sick and wounded being treated at Long Island College Hospital in Brooklyn:

And here’s an article establishing that James W. Saxton of the 103rd Pennsylvania was being treated for “fever” at Brooklyn’s Long Island College Hospital:

Brooklyn was the third largest city in the Union during the Civil War. It had many workers, significant resources, and a substantial industrial base. As a result, many Union soldiers who had been wounded at the front, or were suffering from disease, were sent by ship or rail north (often from Virginia, where many of these men had gone into battle or been camped) to Brooklyn to be treated in hospitals there. If, sadly, they died in Brooklyn, they were typically sent off to Green-Wood Cemetery for free interment in its Soldiers’ Lot–Green-Wood’s trustees had donated that lot, in 1863, as the war raged, for free burial of any soldiers who had died, whether in battle or by disease–in the effort to preserve the Union. There are more than 100 men who died during the Civil War interred in that lot. Times were different back then, and it was rare for the United States government to send a soldier’s body back home to his family. So, in the Soldiers’ Lot lie men from Vermont and Maine and Pennsylvania regiments, who died far from home, in Brooklyn hospitals.

One more article on the goings on at Long Island College Hospital in July of 1862:

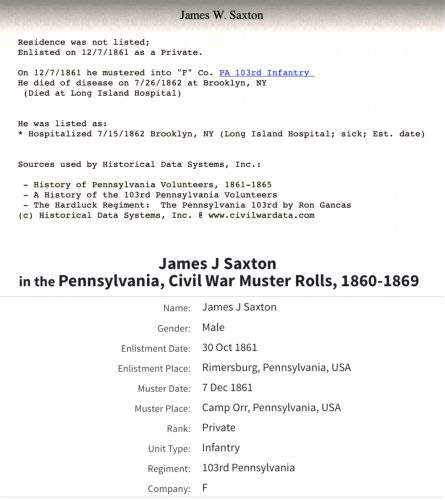

With this information establishing that Green-Wood’s James W. Paxton was likely James W. Saxton of the 103rd Pennsylvania, Sue was then able to find two soldier histories for this man:

Note that the first and more detailed of these two listing states that the soldier, James W. Saxton, was hospitalized on July 15, 1862, at Long Island College Hospital in Brooklyn and that he died there of disease on July 26, 1862–which exactly matched the early newspaper reports above and the information for the “James W. Paxton” who was interred in Green-Wood’s Civil War Soldiers’ Lot on August 2, 1862.

So how did Green-Wood’s records wind up with a misspelling of this man’s last name? It seems to have been a reading/writing error–some clerk along the way–whether military or at Long Island College Hospital or in the undertaker’s office or at Green-Wood–seems to have misread a script capital S as a capital P–an understandable error, given the similarity of those two shapes. Context would not have helped much here–Saxton and Paxton would have been equally likely. Indeed, checking Historical Data Systems, I discovered that 216 men whose last name was Saxton served in the Union armies during the Civil War and 180 whose last name was Paxton also served.

Sue’s discovery had implications beyond simply correcting and completing an online biography. It meant that this patriot, who died in the service of his country, could be properly memorialized, both as to his name and the regiment he served in. You may have noticed in the first image of this post a photograph of a gravestone issued by the Department of Veterans Affairs for James W. Paxton of the 103rd New York Volunteers. That gravestone was obtained by Green-Wood’s Civil War Project, likely in 2007, to mark the grave of what we thought, based on cemetery records, was James W. Paxton of the 103rd New York Volunteers. With the benefit of Sue’s extraordinary research, we now know that the soldier’s name was James W. Saxton (not Paxton) and that he in fact served in the 103rd Pennsylvania Infantry (not the 103rd New York). So, just two days ago, relying on Sue’s research, I sent a long e-mail to the Department of Veterans Affairs, explaining our error and requesting that a corrected gravestone be issued. That department has now approved a replacement gravestone for this soldier, with both his name and regiment corrected: James W. Saxton of the 103rd Pennsylvania Infantry. It should arrive at Green-Wood in about a month.

Green-Wood has also corrected its records to indicate the correct name of this soldier.

Thanks, Sue, for your great work! Another mystery solved!!!