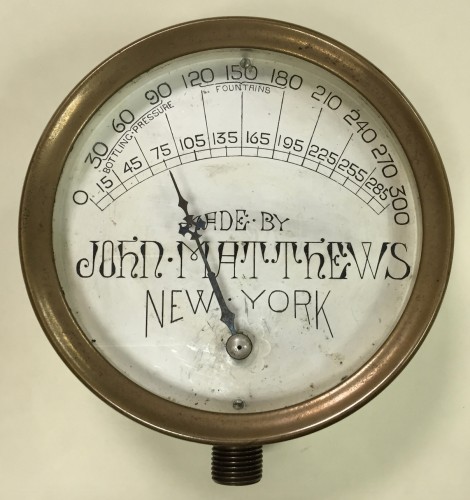

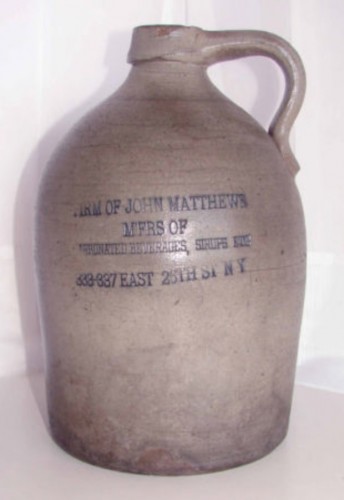

We are regularly adding items to The Green-Wood Historic Fund’s Collections that help us tell the story of the cemetery and/or its permanent residents. Photographs. Books. Prints. Radios. Crocks. Silver. All sorts of things. And now this:

As soon as I saw this object, I knew we had to have it–because of the story we could tell with it–as detailed below.

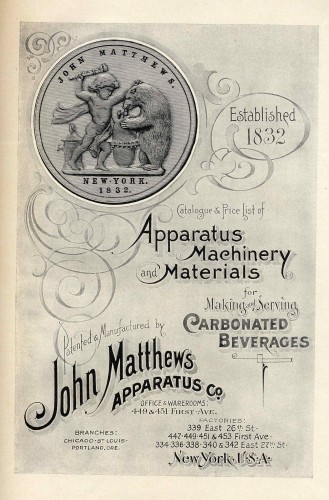

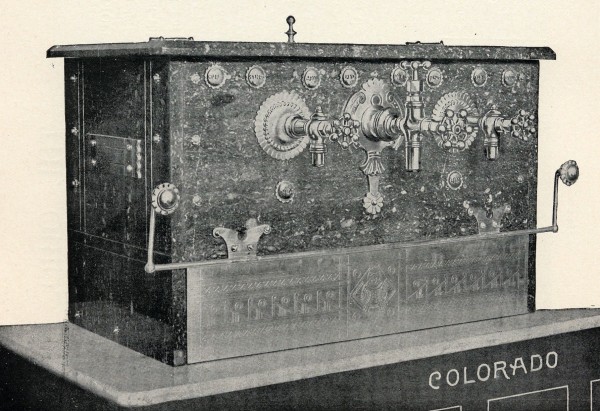

John Matthews (1808-1870) trained in his native England in the manufacture of devices to carbonate drinks. He immigrated to New York City in 1832 and established his business at 55 Gold Street in Manhattan, where he made carbonated drinks popular and manufactured elaborate soda fountains.

When the “Soda Fountain King” retired, his Manhattan manufacturing plant, then on First Avenue stretching from 26th to 27th Street, was immense. Matthews was the largest manufacturer in the soda fountain industry and was known as “the Neptune of the trade.” By the time of his death, more than 500 establishments in New York City alone were using his soda fountains.

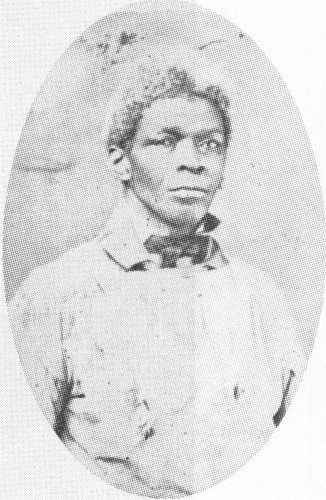

Now back to the Matthews gauge above. “Old Ben” Austen had been enslaved in North Carolina–first working as a field hand, then promoted to a house slave. When his master died, Ben was freed by his master’s widow and came to New York City, where he went to work for John Matthews. He was well-known on the streets of New York, wheeling for the Matthews pushcart soda fountain along the streets for years. During the Draft Riots of 1863, Austen was chased by a mob intent of lynching him. He managed to escape to the Matthews factory and was able to leave there, hidden in one of Matthews’ shipping crates.

Matthews at the time was working at improving soda fountain apparatus–but he was having trouble finding a gauge that would accurately indicate when the appropriate gas pressure–150 pounds per square inch–had been reached in his carbonated drinks. Explosions were all too common. The solution: the thumb of “Old Ben”–who was known for both his intelligence and his strength. He would put his thumb over the release valve–and when the pressure was too great for him to hold his thumb in place any longer, the pressurization was complete. As The New York Times reported, “If his thumb was forced away by the pressure the fountain was charged.” The human safety valve had done his job! And “Ben’s Thumb” became the jargon in the soda water industry for the full pressure.

So, the pressure gauge that you see above is, in fact, a mechanical replacement for “Old Ben’s” thumb.

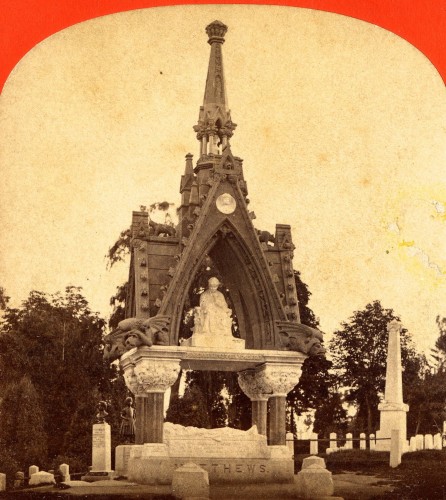

It would be impossible to blog about John Matthews without discussing his spectacular memorial at Green-Wood. It is a wonder! This exuberant work, shown below, was designed by Karl Muller (1820-1887), a German and French-trained goldsmith and sculptor who immigrated to the United States around 1850. Its overall form was of a type typically reserved for royalty, Popes, and the elite.

By 1868, Muller was creating terra cotta (fired clay) sculptures. The whimsical Matthews Monument was executed around 1870 in terra cotta, granite, and marble, for $30,000 ($536,571 in today’s money). It is one of the monuments at Green-Wood that regularly elicits a smile from visitors who come across it. Voted the “Mortuary Monument of the Year” when it was installed at Green-Wood, it is covered with likenesses of members of the Matthews family, evangelists, and hosts of animals and plants. At the first level of the monument, John Matthews is depicted in marble, lying on his back atop a sarcophagus, contemplating bas-relief scenes of his life carved in the stone above him: learning how to make devices to create gas as the product of the chemical reaction caused by combining sulfuric acid (“oil of vitriol”) and marble, bidding farewell to his native Liverpool as he heads to America, imagining new soda water products, and being crowned for his accomplishments. Above him a veiled female figure, seated in an elaborately carved chair, typifies grief–or may be a depiction of his wife. Portraits of his daughters are also incorporated. Gargoyles at each of the monument’s corners catch the rainwater coming off its roof, spitting it out of their mouths.

It is ironic that the chemical process that made Matthews and his family rich–the chemical reaction of acid and marble (he bought tons of marble chips from the construction site of St. Patrick’s Cathedral, as well as scraps from sculptors and monument makers) creating a carbonating gas–is the same chemical reaction that has caused the marble on his Green-Wood monument, exposed over the years to acid rain, to deteriorate, losing much of its detail.

Jeff, It’s great to see more history of Ben Austen. I’d love to hear where you found a more detailed back story.

Unfortunately, that was a while ago–so I don’t recall what my source was.