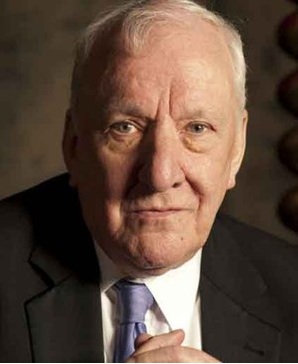

Sir Richard Rodney Bennett, internationally-acclaimed composer, died on Christmas Eve, 2012. His remains will be interred at Green-Wood.

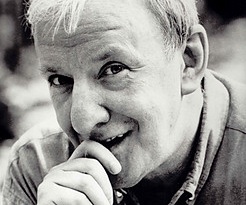

It turns out that Sir Richard and Sir Paul–Paul McCartney, that is–were good friends. Here is Paul’s website, as it appears today, January 10, 2013:

And, also on that home page, “A personal message from Paul on the recent passing of his friend Sir Richard Rodney Bennett” appears; it reads, in part:

It was very sad recently to hear of the passing of Sir Richard Rodney Bennett in New York on Christmas Eve.

Having met him quite a few years ago, we had become good friends as well as sometimes work partners.

I knew of Richard’s work mainly through his film scores, such as ‘Far from the Madding Crowd’ and ‘Murder on the Orient Express’, and his reputation as a great British composer and orchestrator. It was in this last capacity that we came together. Having been coaxed into the world of orchestral music by the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra and Carl Davis when I was asked to write a piece for the Orchestra’s 150th Anniversary, I enjoyed very much working on the Liverpool Oratorio.

. . .

Having collaborated with Carl Davis on the Liverpool Oratorio, I later began to work with others who could help me orchestrate my compositions. This was the beginning of my friendship with Richard Rodney Bennett. I would ring him up, and chat over an idea I’d had to see if he had any interest in helping me translate my ideas for an orchestra. These phone conversations turned out to be fun and quite amusing. Richard showed himself to be quick-witted with a no-nonsense approach for the project.

As we got to know each other better, I would phone him in New York where he lived and worked, sometimes tricking him by impersonating a fictitious long-forgotten friend from his past – “This is Duncan,” I would announce in a thick Scottish accent, “Don’t ya remember me from the Academy?” Being very polite, Richard could be strung along for quite a few minutes before I let him know it was his mad friend doing a silly voice. Eventually he knew who ‘Duncan’ was and I might have to pretend to be the Nigerian Ambassador in order to hear him squirm as he struggled to find a polite way out of this terrible phone call.

We would work either at my place in England or in his, quite modest, apartment in the Upper West Side of New York City. I would be shown in, offered a cup of tea, and having said hello to his favourite cat who roamed the room suspiciously, we would get down to work at his old upright piano. I would play him the piece and often play a recording I had made, on my computer, with a synthesised orchestra. As we went through the music he would make comments and I always had the impression that he knew immediately what voicing and instrumentation would be required.

Composing is one thing, but dividing the parts skillfully across an orchestra; translating the melodies and rhythms into the perfect blend requires a certain special skill that Richard had running through every inch of his body.

These sessions, and the gossip anecdotes, and witty observations which accompanied them, will remain in my memory for a long time and are a large part of what made our time together so special.

Besides classical music, one of Richard’s greatest passions was Jazz and our shared love of the great American composers like Gershwin, Porter, Arlen and many others, led to hours of musical chats, illustrated often by his superb piano playing.

A few times I saw him play in cabaret (at the Algonquin, New York or Pizza On The Park, London) often accompanied by his favourite female Jazz singer which made for nostalgic evenings with Richard running through the chords and melodies of the greats.

We worked together again when in 1997 he orchestrated large parts of my ‘Standing Stone’ and oversaw many of the recording sessions. We often sat, three of us in a row, Richard, John Fraser (the Producer) and myself as a sort of politburo checking in detail the performances of the London Symphony Orchestra. I would sometimes ask him to orchestrate certain sections with hardly any interference from my good self and these were invariably my ‘favourite bits’.

I will miss his gentle but brutally incisive comments on music and life in general. I will miss his intelligence, quick wit and mischievous good humour. I will miss him.

After he was knighted in 1998 I phoned him and this time pretended to be a crass New York business type. “Is this Sir Bennett?” I asked. “Yes it is,” he replied, politely as usual. “I love your toons,” I went on, sensing his momentary embarrassment, “You do great music, I’m a big fan,” and so on and on and it was only when I let him off the hook by revealing who this idiot on the phone was that he cursed me in no uncertain fashion. I’ve laughed a lot. I’ll miss him.

–Paul McCartney, January 2013

Richard Rodney Bennett was born in Kent, England, to a mother had studied musical composition with Gustav Holst and a father who was a chlidren’s book writer. Sir Richard, who was knighted in 1998, was educated in England, where he studied at London’s Royal Academy of Music. But, as he told The Guardian in 2011, “In fact the academy was a disaster. I learned much more in the Westminster music library . . . which was an absolute treasure house of 20th-century music. But London was very exciting. It was cheap and we could live our own lives and be slightly raffish without exactly being bohemian.”

He became one of Britain’s most respected and wide-ranging composers–he described his work as going “in different rooms, albeit in the same house.” He wrote jazz, symphonies, opera, and choral works. His publisher, Gill Graham, was quoted in The Guardian: “He was, I think, the last of his kind. He wrote 32-bar jazz standards, the most complex serial music, and everything in between.” He also performed the Great American Songbook–songs by Cole Porter, George Gershwin, Rodgers and Hammerstein, and others–playing the Oak Room at New York City’s Algonquin Hotel and other venues. And, he was considered by many to be one of the finest jazz pianists of his time.

But it was his movie scores that led to his greatest fame: he earned Academy Award nominations for the scores to “Far From the Madding Crowd” (1967), “Nicholas and Alexandra” (1971), and “Murder on the Orient Express” (1974). He also wrote the scores for “Enchanted April” (1992), “Four Weddings and a Funeral” (1994), and “The Tale of Sweeney Todd” (1998).

Richard Rodney Bennett took up residence in New York City in 1979 and lived there for the rest of his life. His friends, according to The Guardian, knew him as “a fiendish player of Scabble and an enthusiastic creator of delicious Christmas feasts.”

Chris Butler of Music Sales Group lauded his career: “Richard was the most complete musician of his generation–lavishly gifted as a composer, performer and entertainer in a multiplicity of styles and genres.”

There is much of Sir Richard’s work available on Youtube. Here, as a final tribute to him, is “After The Funeral/Funeral Blues,” from his score for the movie “Four Weddings and a Funeral.”

It is a W.H. Auden poem, put to music, and reads:

Stop all the clocks, cut off the telephone,

Prevent the dog from barking with a juicy bone,

Silence the pianos and with muffled drum

Bring out the coffin, let the mourners come.

Let aeroplanes circle moaning overhead

Scribbling on the sky the message He Is Dead,

Put crepe bows round the white necks of the public doves,

Let the traffic policemen wear black cotton gloves.

He was my North, my South, my East and West,

My working week and my Sunday rest,

My noon, my midnight, my talk, my song;

I thought that love would last for ever: I was wrong.

The stars are not wanted now: put out every one;

Pack up the moon and dismantle the sun;

Pour away the ocean and sweep up the wood.

For nothing now can ever come to any good.

Rest in peace, Sir Richard.