I have been leading The Green-Wood Historic Fund’s Civil War Project since September, 2002. With the dedicated help of hundreds of volunteers, we have identified 4,300 Civil War veterans who are interred at Green-Wood, written a biography for each, and obtained 2,000 gravestones from the Department of Veterans Affairs to mark the final resting place of those whose graves were unmarked.

I have been leading The Green-Wood Historic Fund’s Civil War Project since September, 2002. With the dedicated help of hundreds of volunteers, we have identified 4,300 Civil War veterans who are interred at Green-Wood, written a biography for each, and obtained 2,000 gravestones from the Department of Veterans Affairs to mark the final resting place of those whose graves were unmarked.

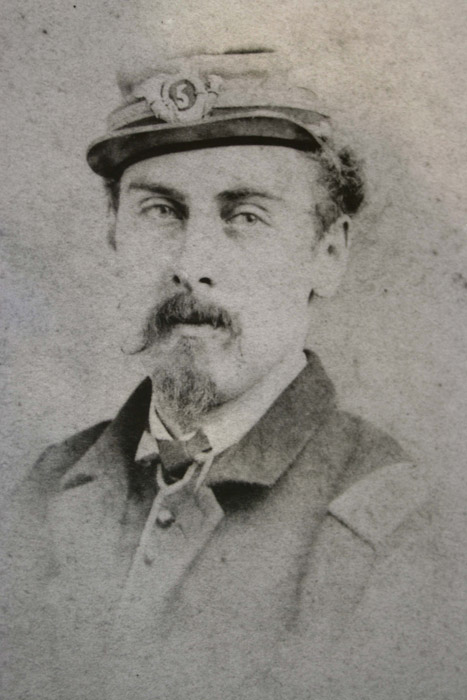

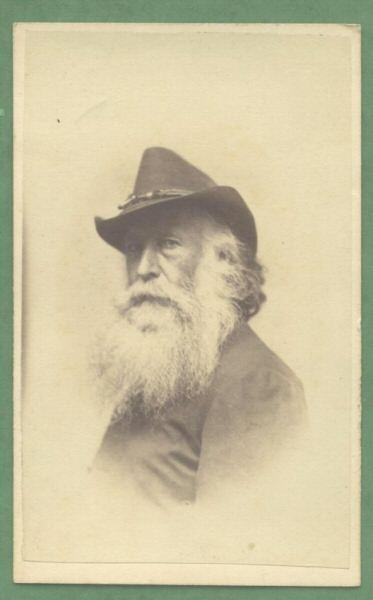

This past Friday, I submitted an application on behalf of Chaplain Gordon Winslow (pictured above) for a gravestone. He and his son, Cleveland, made the ultimate sacrifice for their country–they gave their lives during the Civil War. Though Chaplain Winslow’s wife and children are interred at Green-Wood, he died during the Civil War and his body, tragically, was never recovered (as is explained below). Hopefully we will soon have a marker at Green-Wood, in the Winslow family lot, to honor his service.

Here is an excerpt about Chaplain Gordon Winslow and his son, Colonel Cleveland Winslow, from my book, Final Camping Ground: Civil War Veterans at Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery, In Their Own Words (published by The Green-Wood Historic Fund in 2007, and available, if I might say so, for purchase on the Green-Wood Cemetery website: https://www.green-wood.com/).

Father and Son, Making the Ultimate Sacrifice for their Country

Early June, 1864

Virginia

Cleveland Winslow (1836-1864) was born in Massachusetts, received a college education, worked as a merchant and served for seven years in the 71st New York State Militia during the 1850’s. When the Civil War began, he enlisted in the 5th New York Infantry (Duryée’s Zouaves) as one of its original captains. General George Sykes said of the 5th New York, “I doubt whether it had an equal, and certainly no superior among all the regiments of the Army of the Potomac.” Winslow commanded Company K at Big Bethel. He was also in command at Hanover Courthouse, distinguished himself at Gaines’ Mill, commanded skirmishers at Malvern Hill, commanded the 5th at Manassas Plains (where his horse was killed by seven bullets), and was the major in command of the 5th at Antietam. Promoted to colonel in 1862, he commanded the 5th at Groveton (as part of the Battle of Second Bull Run). It was there that his regiment, in 10 minutes, was overrun by a vastly superior Confederate force, and lost 297 men, including 124 killed, the greatest number of fatalities of any regiment during the Civil War. At times he commanded Sykes’ Division and a brigade. He was known as a flamboyant leader and a stern disciplinarian.

Cleveland Winslow (1836-1864) was born in Massachusetts, received a college education, worked as a merchant and served for seven years in the 71st New York State Militia during the 1850’s. When the Civil War began, he enlisted in the 5th New York Infantry (Duryée’s Zouaves) as one of its original captains. General George Sykes said of the 5th New York, “I doubt whether it had an equal, and certainly no superior among all the regiments of the Army of the Potomac.” Winslow commanded Company K at Big Bethel. He was also in command at Hanover Courthouse, distinguished himself at Gaines’ Mill, commanded skirmishers at Malvern Hill, commanded the 5th at Manassas Plains (where his horse was killed by seven bullets), and was the major in command of the 5th at Antietam. Promoted to colonel in 1862, he commanded the 5th at Groveton (as part of the Battle of Second Bull Run). It was there that his regiment, in 10 minutes, was overrun by a vastly superior Confederate force, and lost 297 men, including 124 killed, the greatest number of fatalities of any regiment during the Civil War. At times he commanded Sykes’ Division and a brigade. He was known as a flamboyant leader and a stern disciplinarian.

Cleveland Winslow was appointed colonel of the 5th Veterans Regiment on May 25, 1863, and worked tirelessly to recruit men for that regiment. While he was recruiting in New York City, the Draft Riots broke out. Winslow issued a call in newspapers for his veterans and citizen volunteers, organized them the next morning with some soldiers and took on the mob with howitzers and artillery firing canister. One veteran, a member of the mob wearing a 5th New York fez and carrying a Sharps rifle, tried to shoot Winslow off of his horse; he missed and hit Winslow’s horse, and was then shot down by a sergeant. Winslow repeatedly ordered that canister and rifle volleys be fired into the mob after his men were surrounded.

After the Draft Riots, Winslow resumed his efforts to organize the 5th New York Veterans, enrolled himself on October 25, 1863, and mustered in as its lieutenant colonel. Severely wounded in the left shoulder on June 2, 1864, at the Battle of Bethesda Church, Virginia, Winslow had surgeons clean his wound and place his arm in a sling, then returned to the battle. But, as he grew weaker from loss of blood, he was ordered to the rear. It was there that his father, the Reverend Gordon Winslow (1803-1864), an Episcopal minister who had served with his son in the 5th New York Infantry (Duryée’s Zouaves) and then joined his son in its successor regiment, the 5th New York Veterans, serving as chaplain in both regiments, found his wounded son and tried to nurse him back to health. Reverend Winslow closed his account of June 2 with “Cleve was wounded.” On the next day, he wrote, “Went over to find Cleve; found him in a cellar of a house, which was being shelled, on our right.” He continued, “Rode all day to the several hospitals . . . brought Cleve to the 6th corps hospital and stayed with him overnight.” Reverend Winslow described Cleve’s “wound in the left shoulder, minie ball, making exit from the back,” and reported that “[t]he wound was much inflamed by his return to the field, after being dressed. He passed the night comfortably . . . . I slept on the ground under the same fly.”

Accompanying his wounded son on the hospital transport ship Mary Ripley, which was carrying them to a hospital, the Reverend Winslow, described in one press account as having the “tenderness for his child equaled [to] that of a mother,” went on deck to get water for his horse, Captive. To do so, the Reverend threw a bucket overboard at the end of a rope into the fresh water of Potomac River. The Reverend Winslow, who had written from the camp of the 5th in July, 1861, that “I am determined to stick to the war to the last,” was never seen again; the drag from the bucket in the water as the ship proceeded apparently pulled him overboard and he drowned.

After Reverend Winslow’s death, someone wrote in his journal: “AT HOME IN THE PARADISE OF GOD ,” then this: “Dr. Winslow was spared the agony of knowing the extent of his son’s wound—a gun-shot fracture of the left shoulder—which resulted in the death of the Colonel on the 7th of July, 1864. at the Mansion House Hospital, Alexandria, V[irgini]a.”

Colonel Cleveland Winslow and his brother, Gordon Winslow, Jr. (1838-1896), who also served in the 5th New York Veterans (and other regiments) and rose to the rank of major by brevet, are interred in lot 3909 at Green-Wood Cemetery. Their mother, who went to Virginia with her sons and husband and served as a nurse, is interred beside them. But the Reverend Winslow is not; his body was never recovered from the Potomac River. Here’s another photograph of Rev. Winslow. May he rest in peace.

Colonel Cleveland Winslow and his brother, Gordon Winslow, Jr. (1838-1896), who also served in the 5th New York Veterans (and other regiments) and rose to the rank of major by brevet, are interred in lot 3909 at Green-Wood Cemetery. Their mother, who went to Virginia with her sons and husband and served as a nurse, is interred beside them. But the Reverend Winslow is not; his body was never recovered from the Potomac River. Here’s another photograph of Rev. Winslow. May he rest in peace.