In Saturday’s New York Times, in a front page article about Attorney General Andrew Coumo’s announcement of his candidacy for New York’s governorship, this was found: “Appearing in front of the former Manhattan courthouse named for Boss Tweed, the corrupt political boss of Tammany Hall, Mr. Cuomo told a crowd of supporters: “Unfortunately, Albany’s antics today could make Boss Tweed blush. Our message today is simple. Enough is enough.”

In Saturday’s New York Times, in a front page article about Attorney General Andrew Coumo’s announcement of his candidacy for New York’s governorship, this was found: “Appearing in front of the former Manhattan courthouse named for Boss Tweed, the corrupt political boss of Tammany Hall, Mr. Cuomo told a crowd of supporters: “Unfortunately, Albany’s antics today could make Boss Tweed blush. Our message today is simple. Enough is enough.”

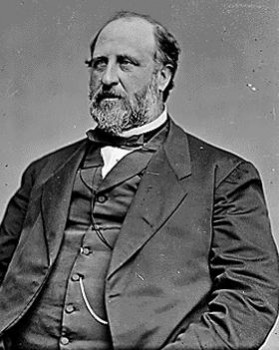

Amazingly, almost a century and a half after his death, William M. Tweed, permanent resident of section 55, lot 6447 at Green-Wood Cemetery, still reigns as the epitome of civic corruption. Politicians have come and gone, but none has matched Tweed’s legacy. And, though he stole hundreds of millions in day-to-day corruptions, nothing matches the Tweed Courthouse, on Chambers Street, as the symbol of Tweed’s corruption.

Here’s the courthouse, and it really doesn’t look too shabby. After all, two of the talented architects who worked on it, John Kellum and Griffith Thomas, also are interred at Green-Wood. So that’s a plus. But then think about what this thing cost. Here’s the account in my book, Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery: New York’s Buried Treasure (have I mentioned it’s for sale at the Green-Wood Historic Fund bookstore?–click here to order one NOW!):

Here’s the courthouse, and it really doesn’t look too shabby. After all, two of the talented architects who worked on it, John Kellum and Griffith Thomas, also are interred at Green-Wood. So that’s a plus. But then think about what this thing cost. Here’s the account in my book, Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery: New York’s Buried Treasure (have I mentioned it’s for sale at the Green-Wood Historic Fund bookstore?–click here to order one NOW!):

It has been estimated that during his reign of corruption, William Magear (“Boss”) Tweed, the “Tiger of Tammany,” and his political cronies stole $200 million (the equivalent of about $3.5 billion in today’s money) from the citizens of New York. Tweed, serving as New York State Senator, Democratic County Chairman, School Commissioner, Deputy Street Commissioner and President of the Board of Supervisors, had untold schemes to put public money into his own pockets and those of his friends. But his greatest single thievery project was the New York County Courthouse on Chamber Street, described at the time as “The House that Tweed Build.”

In 1858, the New York State Legislature approved “a sum not exceeding $250,000” (close to $6 million today) for the construction and furnishing of New York City’s courthouse. This was a substantial sum in an era when school teachers were making only $300 per year. But that appropriation was nothing compared to what the Tweed Ring had in mind for their grandest exercise in graft. In an era in which all of the land for Central Park cost New York City $5 million, and the elaborate St. Patrick’s Cathedral cost $2 million to build, the Tweed Courthouse wound up costing New York’s taxpayers $12 million (equivalent to about $200 million today). More money was spent to build the Tweed Courthouse than was spent to construct the United States Capitol. In fact, the Courthouse was the costliest public building that had yet been built in the United States.

It is no mystery why the Tweed Courthouse cost so much to build: bills were wildly inflated in order to provide generous sums for kickbacks. Billings for plaster work by Andrew J. Garvey, the grand marshal of Tammany Hall, who was dubbed the “Prince of Plasterers,” were $3 million; much of that was for Garvey’s repairs of his own work. The final expenditure for brooms for the courthouse, $250,000, matched the total originally budgeted for the entire building. Enough carpet was ordered (close to $5 million worth) to cover all of City Hall Park three times, and many of the companies billing for carpeting did not even exist. Thermometers for the courthouse cost $7,500. Three tables and four chairs were billed at $179,729. Over $1 million was paid for plumbing work. The marble for the courthouse was purchased from a quarry in Massachusetts that Tweed himself just happened to have recently purchased; quarrying that marble cost more than it had cost to build an entire courthouse in Brooklyn.

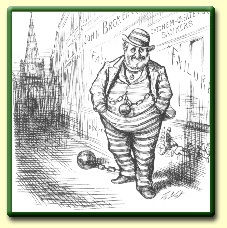

After a campaign led by The New York Times and cartoonist Thomas Nast ofHarper’s Weekly, Tweed was arrested for his crimes in 1871, and the Tweed Ring was finally forced from power. Tweed went to trial in November, 1873; ironically, his trial was held in the still-incomplete courthouse. Tweed was convicted of 204 counts, but he escaped from custody and fled to Spain, only to be recaptured by Spanish officials who, relying on a Nast cartoon, recognized him. Tweed was brought back to New York City, spent some time in prison, and died in 1878.

–from Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery, New York’s Buried Treasure by Jeffrey I. Richman

And here’s my favorite Thomas Nast cartoon of Tweed. Law and order finally caught up with Tweed; he was jailed for his thievery, and died, according to cemetery records, at the Ludlow Street Jail (though, in fact, pulling one final string, he was paroled so that he could die at home).

UPDATE: “The Boss” (no, not Springsteen) is in the news (the Daily News, to be precise) again today, July 1. Click here to see his latest mention. Even his gravestone at Green-Wood gets a little publicity in this article. According to Ken Ackerman, author of Boss Tweed, though Green-Wood Cemetery had rules that barred burials of anyone executed for a crime or who died in jail, that bar was waived in Tweed’s case (according to cemetery records, he died at the Ludlow Street Jail) when the Tweed family agreed to scale back the Boss’s monument to a fairly modest piece of granite.

UPDATE: “The Boss” (no, not Springsteen) is in the news (the Daily News, to be precise) again today, July 1. Click here to see his latest mention. Even his gravestone at Green-Wood gets a little publicity in this article. According to Ken Ackerman, author of Boss Tweed, though Green-Wood Cemetery had rules that barred burials of anyone executed for a crime or who died in jail, that bar was waived in Tweed’s case (according to cemetery records, he died at the Ludlow Street Jail) when the Tweed family agreed to scale back the Boss’s monument to a fairly modest piece of granite.

Andrew j garvey the plaster Prince was my great great grandfather. It’s odd how you can find financial records such as tax assessments. You cannot find photos or even what happened to him.

After they were caught.

Does anybody know what happened to Andrew?

It looks like he is interred at Woodlawn Cemetery in The Bronx. You will find his obituary here: https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/search?firstname=andrew&middlename=j.&lastname=garvey&birthyear=&birthyearfilter=&deathyear=&deathyearfilter=&location=&locationId=&memorialid=&mcid=&linkedToName=&datefilter=&orderby=r&plot=&page=1#sr-92362011