Sometimes, as we peruse Green-Wood’s massive archives, with millions of documents chronicling the lives of the 574,000 souls who are interred here, something unusual catches one’s eye. So it was for volunteer Jim Lambert, who recently worked for months recording the information from Green-Wood’s chronological books pertaining to each of the 1400 individuals who are interred in Green-Wood’s Freedom Lots–lots which offered burials for people of color in the 19th and 20th centuries. One day Jim came across the 1910 burial record for a Ronda Rangit, who was noted as having been born in Borneo and having died at Dreamland, the famous Coney Island amusement park. Jim brought this to my attention, and I thought there might be an interesting story there. As you will see below, indeed there was.

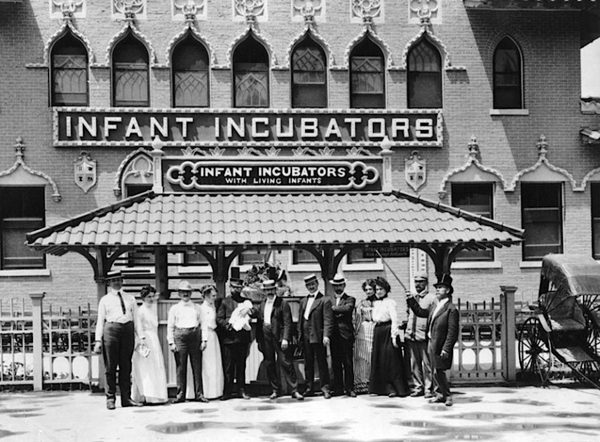

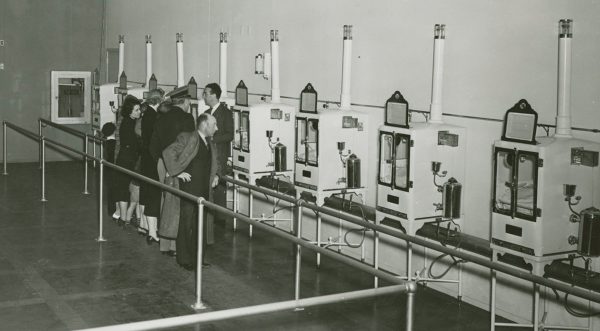

In the early 20th century, Coney Island was a place of mass entertainment–much of it very low brow. There were rides of all descriptions, many of which would never be allowed to operate today because of safety concerns. And there were entertainments that many would find so offensive today that they would never see the light of day. Imagine a Lilliputian Village, which opened in Coney Island in 1904, inhabited by small people recruited from circuses and freak shows. Or how about the Human Roulette Wheel, a large rotating disc designed to push strangers against each other in forced intimacy? At Dreamland, in 1903, you could pay your money to visit Dr. Martin Couney’s Infant Incubators, advertised as “With Living Infants,” where premature babies in need of medical treatment in an incubator (not accepted medical practice back then, and still decades before neonatal treatment was offered in hospitals) were put on public display–surrounded by attendants dressed as nurses and doctors.

Re-creations of disasters also were big entertainment–how about a visit to the Johnstown Flood, where you could revel in the death of the more than 2000 people who had died just a few years earlier, and thrill to the tragic disaster that had befallen them? Or perhaps a visit to the Galveston Flood, where 6,000 perished?

How about the Blowhole Theater, a big hit for George Tilyou and his Steeplechase Park, where crowds packed bleacher seats to watch as unsuspecting women leave the Steeplechase Ride only to have a blast of air from hidden jets blow their skirts up over their heads while clowns with electric prods chased male patrons around the stage?

Certainly one of the most offensive concepts for “amusement” at Coney Island was what are now referred to as “human zoos”–villages of people of color, tricked or lured with false promises from their homes halfway around the world to be displayed at Coney Island as human, or other-than-human, oddities for largely white audiences.

So what does this part of Coney Island history have to do with Green-Wood? Well, Green-Wood has strong ties to some of Coney Island’s most prominent enterprises. George Tilyou, who ran Steeplechase Park, and William F. Mangels, who designed and built many of the rides (he invented “The Whip” ride, a staple of amusement parks for generations, and put the gallop into carousel horses) and shooting galleries at Coney Island, are interred at Green-Wood. (I curated an exhibition about Mangels at Green-Wood’s Historic Chapel in 2014.) Charles Feltman, who invented the hot dog, and parlayed that invention into a cluster of huge restaurants, beer gardens, and amusement rides on Coney Island, is also interred at Green-Wood. As is John McKane, the “Czar of Coney Island,” who controlled the politics and much else there for decades (even sending his minions into Green-Wood Cemetery to copy names off gravestones, then register those names to be used for corrupt voting) until law enforcement carted him off to prison. Now the recent discovery at Green-Wood of the burial records for Ronda Rangit–born in Borneo, died at Dreamland–leads us further into a Coney Island story.

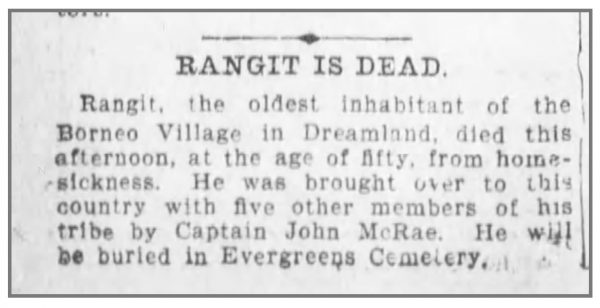

So who was Ronda Rangit? According to Green-Wood’s records, he was born in Borneo and was 53 years old at the time of his death; he died at Dreamland in Coney Island on July 2, 1910, from pneumonia. He was interred in lot 88 (one of the Freedom Lots), grave 70, on July 4, 1910. On July 3, 1910, just two months after the Borneo Village opened at Dreamland, and the day before his interment at Green-Wood, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported his death:

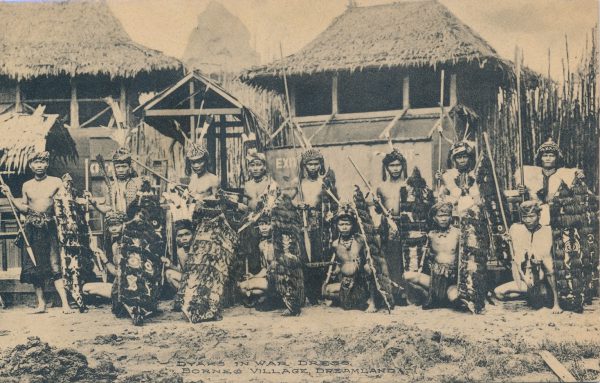

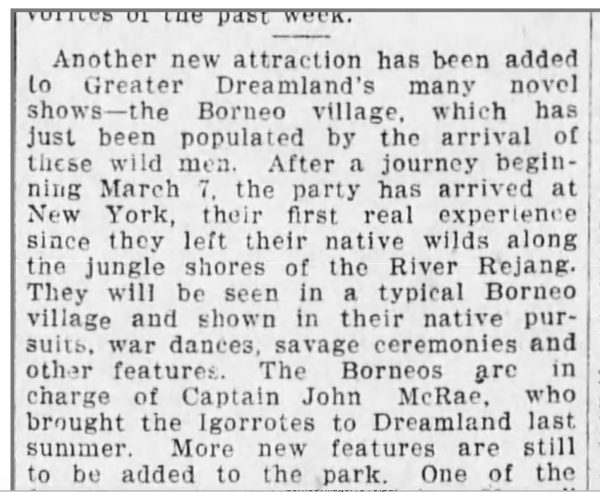

What do we know about the Borneo Village at Dreamland? On May 29, 1910, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported on Coney Island attractions for the upcoming summer season. Don Fulano, “a revelation in equine intelligence,” who “reads, writes, spells,” and solves math problems, as well as “laughs at funny stories when told to him by his press agent” (who doesn’t?), would be exhibited for the coming season. And, the article continued, “In a few more days Dreamland will also add to its attractions a Borneo village, with thirty native warriors, who were brought over here under the direction of Caption John McRae.” McRae, in another newspaper article, is described as a military veteran “who brought the first head hunters to America” (apparently in an earlier excursion).

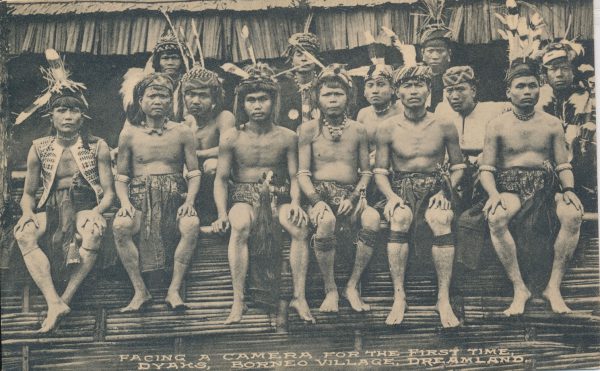

These are rare images of the Dyak tribesmen who made up the Borneo Village.

Perhaps one of these men is Ronda Rangit:

On Sunday, June 12, 1910, this item appeared in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle:

It appears that the Borneo Village was not a hit. It lasted only through the 1910 season; by May of 1911, with Dreamland about to open for its new season, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported that it was time to move on: “[t]he Borneo Village will be replaced by a Curio Village, in which human curiosities have been gathered from the world over.” And the world was a better place for the demise of the Borneo Village.

But the Borneo Village at Dreamland was not an isolated event. Indeed, Harriet A. Washington, in her New York Times review of Pamela Newkirk’s Spectacle: The Astonishing Life of Ota Benga (Ota Benga was a young man from the Congo who was brought to America and displayed as the “African Pygmy” at the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis, then in a cage at the Bronx Zoo with an orangutan, to the jeers of visitors; Benga ultimately committed suicide), wrote:

The internment of “exotic” peoples in expositions and world fairs was no rare event in the 19th century, when Europeans swarmed Africa and other colonial lands in search of “subhumans” to display. Bodies, typically brown and black, were exhibited by scientists as well as impresarios like P. T. Barnum. In fact, Barnum’s first success was an 1830s attraction featuring Joice Heth, fictitiously billed as the 161-year-old “mammy” of George Washington.

We remember Ronda Rangit, who died at a place called Dreamland, so far from his Borneo home, and is interred in the Freedom Lots at Green-Wood Cemetery. May he rest in peace.

The 1910 Daily Eagle article mentions an earlier group exhibited at Coney Island but appears to garble the facts. A group of Bontoc mountain people (Igorot) from the American-controlled Philippines were exhibited at Luna Park, but that was in 1905, not “last summer” as the article states. Their exhibitor in 1905 was Dr. Truman Knight Hunt, not the “Captain John McRae” credited with transporting the Borneo people. The remarkable story of the forlorn Bontocs in America is recounted in page-turning fashion by Claire Prentice in her 2014 book, “The Lost Tribe of Coney Island: Headhunters, Luna Park, and the Man Who Pulled Off the Spectacle of the Century”.

Thank you very much for sharing this information. It gives us a broader picture of these sad events.