William Merritt Chase (1849-1916), who is interred at Green-Wood with his favorite model and wife, Alice Gerson Chase, was one of the giants of American painting. Chase was one of America’s, and the world’s, great painters of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. He painted prolifically in a remarkable range of styles–from Old Master to Impressionist, and a broad range of everyday subject matter–from portraits to public parks to beaches to interiors–over a 40-year career. As D. Frederick Baker has written, “Chase was, and remains, the archetypal cosmopolitan artist, painting contemporary American life as lived by the growing leisure class in America in the late nineteenth century–and certainly the most New York City-centric artist of his day.” Chase also was an extraordinary teacher–he has been called the most important instructor America has ever produced–training and mentoring leading American artists including Edward Hopper, Joseph Stella, Georgia O’Keefe, Charles Sheeler, and Marsden Hartley. Here’s O’Keefe on Chase: “there was something fresh and energetic and fierce and exacting about him that made him fun.”

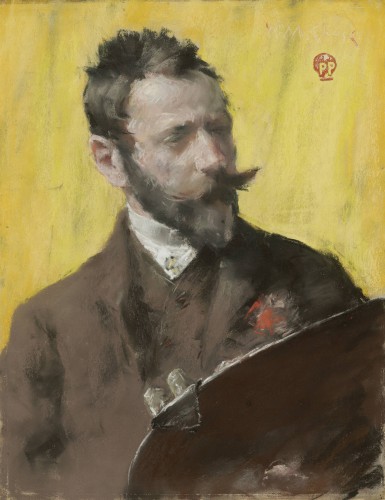

William Merritt Chase (American, 1849–1916)

about 1883

Pastel on paper

An MFA Honorary Trustee and Her Spouse

Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Chase had a big personality; he was flamboyant, ever a showman, but also a very gifted artist. Typically, he wore a top hat, white spats, and a three-piece suit with a carnation in the buttonhole; a black ribbon dangled from his pince-nez and his dramatic beard and upturned mustache were neatly-trimmed.

William Merritt Chase is currently on exhibition at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts (MFA), and continues there through January 16, 2017. It is the first retrospective of Chase’s remarkable career in three decades and features 80 of his finest paintings: landscapes, urban parks, portraits of modern women, and still lifes. The exhibition was organized by the The Phillips Collections in Washington, D.C. (where it already has been exhibited), Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts, the Terra Foundation for American Art, and the Fondazione Musei Civici di Venezia in Venice, Italy. After it closes in Boston, it will be off to Venice for exhibition, opening there in February.

Chase was born in Indiana. As a young man, he showed artistic promise, and was off to Europe in 1872 to study at the Royal Munich Academy. After training there, he made New York his base–renting space at the famous Tenth Street Studio in Manhattan, painting his family and public spaces in Brooklyn, teaching in New York City, and spending his summers in the Hamptons, where he taught and painted. He adapted Impressionism to modern America and lifted world-wide appreciation of American art. He brought budding artists to Europe to expose them to its influence. He founded the Chase School of Art, which since has become the Parsons School of Design. As Erica Hirshler, senior curator of American paintings at the MFA, has said of Chase: “Inspired by the old masters and excited by the beauty he found in the world around him, Chase created bold compositions of everyday subjects, family and friends.”

Matthew Teitelbaum, director of the MFA, writes of Chase: “The expressive range and depth of William Merritt Chase’s work is extraordinary–from his dynamic and varied use of oil paint to his mastery of pastel on paper and canvas–even in the context of the rich chapter of American art from which he emerged.”

Chase painted independent women.

William Merritt Chase (American, 1849–1916)

1884

National Academy of Design diploma presentation, November 24, 1890

Oil on canvas

National Academy Museum, New York

Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. What is remarkable here is the engagement of the sitter; she looks, unabashed, directly at the viewer. Soon after this painting was completed, Chase sent it off for display in Belgium. Of the 20 avant-garde painters who displayed there, only three were Americans–and they all were giants: Chase, John Singer Sargent, and James McNeill Whistler. Whistler’s influence is apparent here in the limited range of colors and the choice of similar colors for adjoining surfaces: the chair and wall.

William Merritt Chase (American, 1849–1916)

1882‑1883

Oil on canvas

The Cleveland Museum of Art, Gift of Mrs. Boudinot Keith in memory of Mr. and Mrs. J. H. Wade

Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Dora Wheeler, the subject, was Chase’s first student, a painter and illustrator. Her blue dress contrasts with the yellow Chinese fabric that frames her. This painting was shown at the prestigious Paris Salon in 1883.

William Merritt Chase (American, 1849–1916)

by 1889

Pastel on paper, prepared with a tan ground, and wrapped with canvas around a wooden strainer

Terra Foundation for American Art, Daniel J. Terra Collection

Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. This painting is a tour de force of color, shape, and the exotic East. Chase was fascinated, as were many of his contemporaries, with Japan; his studio was filled with kimonos, umbrellas, dolls, and more from there. Note that here the female subject, of a non-modern culture, does not look directly at the viewer.

Chase painted still lifes. For much of his career, he feared that his legacy would be nothing but his paintings of fish.

William Merritt Chase (American, 1849–1916)

about 1900

Oil on canvas

The Hayden Collection—Charles Henry Hayden. Here Chase explores sheen, texture, and the arrangement of forms. He was considered as without peer for fish still lifes.

He painted interiors–his own studio was a favorite subject. At the famous Tenth Street Studio Building in Manhattan (built by James Boorman Johnston, who is interred at Green-Wood, and occupied by many other artists who are Green-Wood permanent residents, including John La Farge, Lockwood de Forest, William Holbrook Beard, John Frederick Kensett, John Casilear, and John George Brown). Chase rented the largest studio there–and often used his eclectic collection that filled his studio as a backdrop for his paintings.

William Merritt Chase (American, 1849–1916)

about 1882

Oil on canvas

Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Mrs. Carll H. de Silver in memory of her husband

Brooklyn Museum photograph

Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. From 1878 to 1895, Chase rented the two largest rooms in New York’s famous Tenth Street Studio Building. He filled the space with eclectic paintings and objects he had collected from around the world. It became his stage for invention, for inspiration–serving as the backdrop for more than a dozen of his paintings, as his sales room, and as his place of entertainment. Dogs, monkeys and parrots roamed the space; a serving man’s costume was topped by a fez. By 1895, Chase had decided to move on, closing his studio there and auctioning its contents.

Chase painted Brooklyn–both his family living there and its parks.

William Merritt Chase (American, 1849–1916)

about 1888

Oil on canvas

Lent by the Toledo Museum of Art; Purchased with funds from the Florence Scott Libbey Bequest in Memory of her Father,

Maurice A. Scott

Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Chase married his favorite model, Alice Gerson, in 1887, and the couple moved in with her parents in Brooklyn. Here Chase captures his family at leisure in their Brooklyn backyard: from left to right, their pet greyhound Fly rests, Alice’s sister lies in the hammock, their daughter Cosy sits in the high chair, Alice sits with the baby, and Chase’s sister, Hattie, holds a racquet, a young woman with physical activity in her plans. The painting, with a bright palette, shows a suburban, modern family with leisure time.

In addition to teaching at the Brooklyn Art School and the Art Students League in New York City, as well as the Pennsylvania Academy of Design in Philadelphia, Chase ran a summer painting school out in the Hamptons. There he captured on canvas scenes of Long Island’s east end, often featuring his wife and daughters.

William Merritt Chase (American, 1849–1916)

about 1892

Oil on canvas

Lent The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Bequest of Miss Adelaide Milton de Groot (1876–1967), 1967

Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. From 1891 to 1902, Chase was the director and star attraction at the Shinnecock Summer School of Art. This was the first American art school devoted to plein air painting–painting out of doors. He spent two days a week teaching hundreds of students; the rest of his time was spent with his family or painting, often painting his family in various Hampton locales.

William Merritt Chase (American, 1849–1916)

1892

Pastel on canvas

Terra Foundation for American Art, Daniel J. Terra Collection

©Terra Foundation for American Art, Chicago

Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Here Chase’s wife, Alice, and two of his daughters, enjoy a quiet moment, surrounded by Chase’s elaborate decorations. Chase’s own image joins the family portrait: it appears as a reflection in the armoire doors in the distance.

William Merritt Chase (American, 1849–1916)

about 1896

Oil on canvas

The Halff Collection

Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Here his daughter, Cosy, is about to toss a ring as her younger sisters, Koto and Dorothy, await their turns. The setting is the Chase home in Shinnecock; for Chase, home and studio were one and the same.

William Merritt Chase (American, 1849–1916)

1888

Oil on canvas

The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC, Acquired 1923

Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Here Chase experiments with a large dark space in the middle of the painting.

Chase’s favorite model was Alice Gerson. She became his wife.

William Merritt Chase (American, 1849–1916)

1886

Pastel on canvas

Willard and Elizabeth Clark

Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Alice Gerson was Chase’s favorite model; they married a year after she posed for this painting. She grew up in a family focused on art; her father, Julius, who is interred at Green-Wood in the same lot as her and Chase, was the manager of the New York City art department for lithographer Louis Prang. Here she looks directly at the viewer and at the world–as was common for Chase’s depiction of the modern, engaged woman.

William Merritt Chase (American, 1849–1916)

1892

Oil on canvas

Private Collection

Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Again, the model here is Alice Gerson Chase. This is not just “An Artist’s Wife”–this is THE artist’s wife. To leave no doubt as to her identity, the painting in front of her is one of Chase’s works–it shows Alice and their daughter, Koto, on Shinnecock’s dunes. Alice’s pose is derived from a 17th-century painting by Frans Hals–though Hals typically used that pose for portraits of men, not for that of a modern woman.

William Merritt Chase (American, 1849–1916)

1915‑16

Oil on canvas

Purchase by Richmond Art Museum and gift of Warner M. Leeds

Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. This is one of Chase’s last paintings, completed shortly before his death. He holds palette and brush, still a productive artist. The painting on the easel is in its early stages, holding out hope that much more is to come from the painter. But that was not to be. Chase, in a lecture to his students early in the year of his death, said of this painting, “I have just made a portrait of myself standing with a blank canvas in front of me. This is to be my masterpiece. The ideal and the aim of it all I believe is that you can remain young all the time to the end; always be a fresh fighter, ambitious to the end.”

William Merritt Chase, known to his contemporaries as “The Dean of American Painters,” and his wife, Alice, are interred in section 68, lot 1739, at Green-Wood. The lot was owned by Chase’s aunt at the time of his death. Chase was interred there in 1916, just days short of his 67th birthday. Here is their lot:

The lot holds 29 bodies. Included are 6 Chases and 6 Gersons–members of William’s and Alice’s families, including several of their children. Chase died in 1916. Alice died in 1927, 11 years later. Her last residence was at 234 East 15th Street in Manhattan–on Stuyvesant Square–the same address listed for Chase in 1916, when he died; her death, at the age of 61, was due to carcinoma. Her family asked that Chase’s grave be opened for Alice’s interment; that wish was carried out, and they have lain together for a century. A modest gravestone, carved with their names and life dates, marks their final resting place.

Just days after Chase’s death, The New York Times wrote in tribute:

His gayety of manner was the idiom he used to make us aware of the multitudinous charm of the visible world. Things that would have been lost he saved for us–unconscious momentary attitudes of children, swift changes of color under angles of light that became different angles in the twinkling of an eye, the rhythms of draperies swung by flickering gust of wind . . . . The death of William Merritt Chase removes from the ranks of American artists one whose contributions probably will receive a richer measure of applause in the next century.

Part of that measure of applause, in the next century, is this landmark exhibition of his work.

♦ ♦ ♦

Thanks to volunteer Jim Lambert for retrieving the relevant burial orders for lot 1739.

♦ ♦ ♦

A profusely-illustrated catalogue of the exhibition, William Merritt Chase: A Modern Master, is available in book stores and online. It, also, is a rich measure of applause for William Merritt Chase’s work.

My name is Michael Coomes and I am a retired faculty member from Bowling Green State University. One of my post-retirement volunteer activities is serving as a Docent at the Toledo Museum of Art. In preparation for leading tours, members of my Docent-in-Training class were assigned a research paper. I was assigned William Merritt Chase’s The Open Air Breakfast. I came across your Chase entry on the Green-Wood Cemetery page. On that page you write that in The Open Air Breakfast, “Chase captures his family at leisure in their Brooklyn backyard: from left to right, their pet greyhound Fly rests, Alice’s sister lies in the hammock, their daughter Cosy sits in the high chair, Alice sits with the baby, and Chase’s sister, Hattie, holds a racquet.” I am trying to track down the origin of the claim that the dog is a greyhound named Fly. This claim was also made in a lecture by Dr. Carol Clark, entitled William Merritt Chase and the Commonplace delivered at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston in 2016. I have contacted Dr. Clark but have not heard from her so I am turning to you. The TMA label for the work suggests the dog is a Russian Wolfhound (https://www.toledomuseum.org/art/artminute/aug-12-art-minute-william-merritt-chase-open-air-breakfast). Can you point me in the direction of your source for the name and breed of the dog? I will be delivering a lecture to my docent colleagues on The Open Air Breakfast in the summer and want to have as much accurate information as possible. Thank you.

Hi Michael,

Great to hear from you on this.

The information that the dog in “The Open Air Breakfast” is a greyhound named Fly comes from here: https://www.mfa.org/news/william-merritt-chase

Search for “Fly” or scroll about half-way down the page.

You might also be interested in this: https://thebark.com/content/art-william-merritt-chase

Scroll down and you will see side-by-side photographs of Virginina Gerson and William Merritt Chase, each with a dog. The dog she is with is, I believe, the same one that appears in the painting. It is a bit hard to see in the photo. as reproduced at that link, but in Photographs from the William Merritt Chase Archives at the Parrish Art Museum, image 16, the white flash on the dog with Virginia is visible–as it is in the painting.

I don’t know where the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, got the dog’s name. But I would think it is safe to rely on that information.

-Jeff

Dear Michael D. Coomes!

I’m not an expert on dogs, but who viewed that dog as a wolfhound? Ridiculous.

That dog is apparently a greyhound.

Sincerely, Katalin