There are Green-Wood connections everywhere.

My favorite place to visit: Mount Desert Island, along the Maine coast, on which are located Acadia National Park and the village of Bar Harbor. I’ve been up there many times–probably 25 times over a period of 40 years. And it has always been great.

On my latest trip, I found something new. I had seen the signs for it many times along one of the highways: The Maine Granite Industry Historical Society. It has been there for 11 years now. I just had never been there before.

But one of the National Park rangers praised it, and said a visit was well worthwhile. So I was off to see what I might find. And it is a gem. It is the dream-come-true of Steven Haynes, who seems to do it all–gather photographs, collect tools, give talks to school studends, and entertain visitors with a discussion of one of the lathes in the collections–and how it turns granite columns. Here’s Steven, proudly standing beside a piece of Cadillac Mountain granite that he is making into a gravestone. Steven has been working on this piece for some time now–he told me that he has spent 65 hours polishing it up–and he still has more polishing to do on it, to even the surface out–there’s still a low spot in one of the corners.

Steven really loves granite. He loves showing off the hammers and drills that he has collected. He loves telling the stories of the men who made the granite industry a major employer on Mount Desert Island–he has a map on display of all of the quarries that were being worked there in the 19th century–about 50 of them.

When I first met Steven, he was talking with another visitor about his latest project–he had been contacted by the restorers of the Prison Ship Martyrs Monument in Fort Greene, Brooklyn, to find the quarry from which the original stone had been mined. Steven was able to find that quarry and the restorers got the stone they needed. As Steven explained, this is a new development in granite quarries–those that were abandoned over the years are now being drained and reopened to supply granite for restoration projects across America.

Just one mile from the museum is Hall’s Quarry. It was one of those that was worked for years, but closed long ago. Equipment now lies around, rusting. Today, the quarry is a campground, and the rainwater that has collected in it over the years is now serving as the campground pond.

The museum features quite a collection stereoviews of quarries and their workers. Steven also has a microscope on display,where you can view cross-sections of various granite samples. Very interesting!

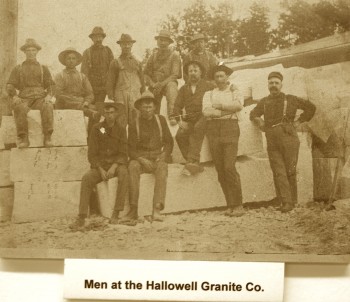

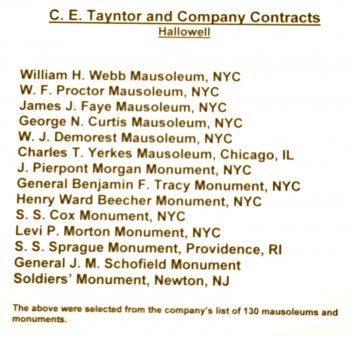

But what really caught my eye was a list of contracts for granite from Hallowell, Maine, for C.E. Tayntor and Company. First of all, I recognized that company name; we had come across it in the last few months when volunteers worked on the records of the Presbery Leland Company, a New York City monument company that ordered granite from Tayntor. Here’s a photograph of the men of the Hallowell Quarry, on display in the Granite Museum. Perhaps one or several of these men cut granite that became a Green-Wood Cemetery gravestone.

As I mentioned above, I am a great stereoview enthusiast. I have been a member of the National Stereoscopic Association for years and have been collecting stereoviews of New York City and other places for more than 30 years. Reading my way through the Granite Museum, I noticed that Maine granite had been used in New York City’s old post office, which was located on the southern part of City Hall Park in Manhattan. I happen to have several stereoviews of that building under construction, circa 1870, with the Maine granite laid out on the construction site, ready to be installed. I told Steven I would make him copies of those photographs if he was interested–and was he excited!

Granite, of course, has played a huge role at Green-Wood. In the 1830s, marble was all the rage in New York City’s cemeteries. It was white, it was pristine, and it was easy to carve because it was soft. Sculptors created great carvings with it. But, as the 19th century progressed, granite became more and more popular as the stone for gravestones. It came in various colors and it was a tough material. Many of Green-Wood’s gravestones are of granite. Here’s Nathaniel Currier’s gravestone, a very common gray, almost black, granite.

Quincy and Westerly granite were used in the Burnham lot (near Battle Hill). The base of the central monument in that lot, a gray stone, is Quincy granite (as is the stone curb around the lot). The carved figure is a Westerley granite, which is an off white or tan. This monument was cleaned a few years ago; until that cleaning, a century’s-worth of dirt hid the fact that two different granites had been used there.

The carved figure on top is also of significance. It was not until 1890 that the firm of Ingersoll Rand started marketing pneumatic tools for carving granite. Before that, marble was the material of choice for cemetery sculpture–it was soft and had a wonderful white color to it. But marble had one very big problem: it deteriorated badly when exposed to acid rain. So, quite a few of the marble monuments at Green-Wood are now unreadable, after exposure for over a century. In contrast, as Steven told me, “Granite is forever.” A very hard material, it lasts and lasts and lasts. I am often asked, on Green-Wood tours, about granite monuments that look new. But, of course, many of them have been out in the weather for over a century–they just look new because granite is so hard that it survives so well. Granite could be carved before these power tools were invented, but it was very slow going to do so by hand–and high prices reflected the labor intensity of the work. New power tools made durable granite readily available at reasonable cost.

Here’s the Beecher monument mentioned in the list at the museum. This is actually the back of this gravestone–the inscriptions for Henry Ward Beecher, “The Most Famous Man in America,” according to Debby Applegate in her Pulitzer Prize winning history, and his wife Eunice, appear on the other side.

And here is a wonderful example of Quincy granite in the Howe family lot. The Granite Museum has many samples of granite, quarried in Maine, Vermont, and other places. Here’s a sample of Quincy granite on display.

Ever been to the Granite Museum in Stonington, on Deer Isle? A gem. Stonington and the islands out in the Thoroughfare were also sources of stone for large projects in the 19th century and one of the quarries was re-opened to provide stone for Lincoln Center.

Thanks! I will try to get to Stonington on my next Maine trip. Your note about Lincoln Center is very interesting, and consistent with what Steven told me.

Jeff, thanks so much for posting this blog, it’s great! Steve and I would love to visit your cemetery one day and identify the Maine granite tombstones. There were many granite companies that had monument shops in NYC in the 1800’s so we know Maine granite is in most cemeteries in NY.

Steve just received an order for a monument from the Crotch Island, Stonington granite to be placed in a local cemetery and another of the Red Beach stone that will be erected in NYC. Will keep you posted on this one. Please keep in touch!

Steve and Juanita